Hello readers,

I am back with new sprigs of thought, and The Sentinel newsletter to make sense of this increasingly tumultuous world. Thank you for your support and your patience. - Senthil

Many workers are being asked to return to office (RTO) all five days. I shall start with a confession. In 2023 (seems eons ago), I wrote a post on Work From Home in which I proclaimed that … Hybrid is the way!

Post-pandemic, in the age of weird simultaneous genuflection and flexing by the CEOs, many employees are increasingly asked to Return to work (RTO). When did this trend start? Marissa Mayer in 2013. I like to say (only half jokingly) that Marissa walked so that all Tech CEOs could now run.

In case you are wondering, Marissa Mayer now heads an AI company called Sunshine (which recently released an automated photo-sharing app called Shine to mixed reviews). Ironically, I couldn’t find much about the remote work policy at Sunshine.

Anyway, it is almost routine now that CEOs are pressing hybrid workers to return full time to office. Here is Andy Jassy (Amazon):

Before the pandemic, not everybody was in the office five days a week, every week. If you or your child were sick, if you had some sort of house emergency, if you were on the road seeing customers or partners, if you needed a day or two to finish coding in a more isolated environment, people worked remotely. This was understood, and will be moving forward as well. But, before the pandemic, it was not a given that folks could work remotely two days a week, and that will also be true moving forward—our expectation is that people will be in the office outside of extenuating circumstances (like the ones mentioned above) or if you already have a Remote Work Exception approved through your s-team leader.

Here is Sergey Brin (cofounder of Google), according to New York Times:

“I recommend being in the office at least every weekday,” he wrote in a memo posted internally on Wednesday evening that was viewed by The New York Times. He added that “60 hours a week is the sweet spot of productivity” in the message to employees who work on Gemini, Google’s lineup of A.I. models and apps.

Every weekday. At least! Reminded me of the cult classic, Office Space, directed by Mike Judge, which came out in 1999. (1999 was such a great year for movies, by the way). In the film, Boss Bill Lumbergh played by Gary Cole asks the protagonist Peter Gibbons to show up at work on Sundays too. Bill also hires some “efficiency consultants” to improve the workplace. (How contemporary!)

Brin thinks 60 hours at office is the sweet spot. However, Narayana Murthy (founder of Infosys) disagrees. He believes that the sweet spot is more like 70 hours in office. Why? To combat poverty. Here is the CIO magazine:

Speaking at the Indian Chamber of Commerce centenary on Sunday, the billionaire argued that 70-hour workweeks are necessary because several hundred million Indian citizens live in poverty. His argument is that those who have jobs should work long hours and embrace entrepreneurship to create jobs for others.

In comparison, Wall street bankers seem quite reasonable. JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon is a fan of RTO on all five days, and was unusually snippy in a Q&A session (source: Quartz):

At the time, Dimon said, “Don’t give me the s— that ‘work from home Friday’ works.” His language soured again when addressing an employee petition to reinstate hybrid work, saying, “I don’t care how many people sign that f—ing petition.”

In the face of all the data on how Americans are working harder than ever, it seems like Tech has thrown in the towel on reinventing work, and surrendering to the old notions. When I lived on the west coast, I met many folks who were into the science of 8-hours of sleep every night, and working out everyday to get ripped like RFK Jr. I don’t know how that approach squares up with the sweet spot of 60 hours in office plus the glorious hours spent in traffic on US-101.

In the optimistic early days of Web 2.0, Tech people talked about how the internet will release us all from the drudgery of workplace. It made me think of the doyen of valley learning culture, Mr. Tim Ferriss.

We can all agree that Tim was on to something, but he wasn’t preaching something new. Wise(r) men had said similar things before. In Harper’s Magazine in 1932, in “In Praise of Idleness”, Bertrand Russell proposed that we should work for four hours a day.

If the ordinary wage-earner worked four hours a day there would be enough for everybody, and no unemployment — assuming a certain very moderate amount of sensible organization. This idea shocks the well-to-do, because they are convinced that the poor would not know how to use so much leisure.

In America, men often work long hours even when they are already well-off; such men, naturally, are indignant at the idea of leisure for wage-earners except as the grim punishment of unemployment, in fact, they dislike leisure even for their sons. Oddly enough, while they wish their sons to work so hard as to have no time to be civilized, they do not mind their wives and daughters having no work at all.

May be 4-hour work days are for middle-of-the-road average guys and unsuccessful chumps. Not for path-breakers. So, I chuckled when June Huh, Princeton Professor and the recipient of 2022 Fields Medal, probably the most prestigious prize in Mathematics, declared that in his Quanta magazine interview that he works only 3 hours a day!

On any given day, Huh does about three hours of focused work. He might think about a math problem, or prepare to lecture a classroom of students, or schedule doctor’s appointments for his two sons. “Then I’m exhausted,” he said. “Doing something that’s valuable, meaningful, creative” — or a task that he doesn’t particularly want to do, like scheduling those appointments — “takes away a lot of your energy.”

Now is that model even replicable? What does doing good work mean?

Search for Metrics

The biggest impediment that hybrid work faces in workplace is disbelief. The disbelief that it can work.

No leader seems to believe that hybrid is a good way to get things done. What if engineers at home really only code for an hour, attend zoom calls and then goof off moonlighting, watching Netflix, or worse, training for the Ironman?

We don’t know much about white collar productivity. So, many CEOs emphasize the only metric that is measurable with a high degree of confidence — the number of hours logged. Critically, measurement of hours is accurate only if employees are in the office. So the thinking goes: “Back to Office Folks! (So that we would know how much you work).”

A colleague of mine remarked that Tech CEOs are leading us back to 996 work culture, still somewhat widespread in Tech world in China. In fact, so prevalent at one point that CCP under Xi Jinping thought that 996 (along with videogames) was a malaise plaguing the society, and came down hard on many tech firms and corporations.

Yet it persists. Amazon CEO Andy Jassy’s note is a good example of worshipping the metric of office work. In 2023, Jassy had argued that “Collaborating and inventing is easier and more effective when we’re in person. .. Learning from one another is easier in-person.” In 2025, gone are the laudatory notes on office interaction burnishing creativity. Words like creativity and learning are absent in the 2025 missive. Instead, there was “desk arrangements” (emphasis mine).

We understand that some of our teammates may have set up their personal lives in such a way that returning to the office consistently five days per week will require some adjustments. To help ensure a smooth transition, we’re going to make this new expectation active on January 2, 2025. Global Real Estate and Facilities (GREF) is working on a plan to accommodate desk arrangements mentioned above and will communicate the details as they are finalized.

It appears that everyone is falling into the trap of counting hours or days as a metric. One way (perhaps, the only way) to increase the number of weekly hours, is to demand that everyone come back into office for five days.

Why are CEOs insisting on 5-day return?

In fairness to the CEOs, leadership thrives on clear directives. Asking employees to be back at work is a clear directive. In contrast, hybrid work policy is a wishy-washy mixed equilibrium. Mixed equilibria are just hard to implement with any degree of fairness. We have very little evidence of successful implementations of mixed strategies in social life. CEOs can’t have some employees show up in office while others stay in the comfort of home-office. Most firms are trapped between standardization (which allows for a better coordination) and flexibility (which humans yearn).

In my earlier post, I had described work from home problem as a Battle of Sexes game (a game in which the employers and employees want different things and cannot coordinate easily). We are just living through the days in which those preferences are heading on a collision-path. Nowhere is the problem more persistent than in the Tech world. Particularly, Tech (followed closely by Finance) has the highest proportion of people who are in hybrid work mode (See picture below).

All problems point to the permanent struggle: How does one measure workplace productivity in white-collar jobs? CEOs love to talk about hours in office because that is the easiest thing to measure. Even though it is not even a good metric for good work.

Every CEO knows that more hours at disposal, the more likely the goal is reached. Strictly speaking, most of those additional hours won’t be productive. In fact, even more hours will be wasted when all workers work longer hours. However, having that excess work time (capacity or resources) is great for reaching company goals. The real problem occurs after reaching the goal. How do we recognize and reward good employees from bad employees?

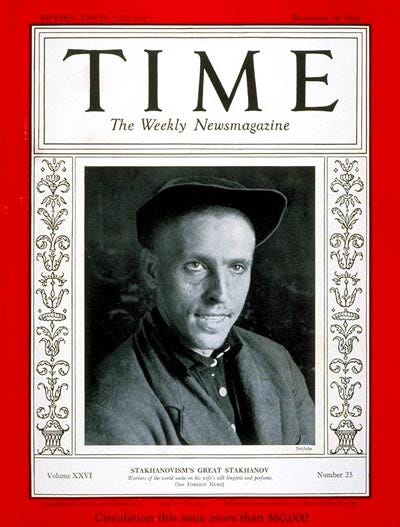

It is easy to calibrate productivity in blue collar labor: In 1930s, Stalinist regime found in a humble Russian miner Alexei Stakhanov a blue collar hero. Stakhanov apparently mined 227 tons of coal in a single shift, and even became the symbolic man on the cover of Time Magazine.

It’s been nearly a hundred years since then, and even today measuring white collar employee productivity faces two problems: First, there is no good universally accepted objective metric for white collar productivity. Second, firms don’t like to use subjective metrics. So, they end up doing the next best thing: Pretending that subjective metrics are actually objective. They do the pretending by using terms like people analytics. People Analytics is mostly just a cooler name for repackaged old-fashioned HR management.

Old fashioned HR (i.e, people to people) management is a good thing! We should promote some classical subjectivity in organizations (like letting people work hybrid, one or two days). It is okay to live with some residual ambiguity when it comes to white collar productivity.

Performance Subjectivity is OK.

Most companies rely on manager appraisals for performance, but every manager is different. So, even performance metrics are subjective. Morris Chang (founder of TSMC) famously said (on Acquired Podcast) that “[Laying people by their performance ratings] would not be a credible way to do things” because it is subjective.

Morris Chang: When the company decided to have a layoff, the CEO conferred with the top managers who included me, and their first reaction was exactly the same. I’m talking about the early 70s. Their first reaction on who to lay off was exactly the same as what our TSMC CEO did in late 2008–2009, which was go by performance.

Now, I was the only one at Texas Instruments in the early 70s that said, no, that would not be a credible way of doing it. People would not respect us if we lay off by performance ratings.

[…]

Morris: Because it’s very subjective. The performance ratings are done by everyone’s own supervisor. Seven hundred worst-performing people in the company. Who gave the 700 people the bad ratings? Seven hundred supervisors. Very subjective.

It appears the aversion to subjectivity has driven us closer to RTO. So where are we now in our journey to rethink our workplaces?

Meta is one of the few bigger companies that has continued with 3-day-at-office hybrid work policy. Zuckerberg has reportedly said “status quo is fine”. I don’t know if it is a masculine move, but it is certainly against the grain, with the current trajectory bends towards RTOs. The future of hybrid work looks more iffy than last year.

Only recently, we were reimagining workplaces to manage professional and creative work. Now, the search for shortcuts has overpowered us.

We have sacrificed the need for measurability for the ease of measurability.

Excellent piece about a prescient topic.

I agree with your conclusion that there is a need to measure productivity, and it is this lack of an objective measure which makes the RTO decision hard to make.

The most common methodology I have seen at technology firms is some version of the Agile methodology which recommends dividing work into smaller tasks called stories (a repurposing of the small batch sizes idea from Lean ) and measuring the quantum of work by 'story points', indicating the effort required to complete the work by an individual. And then measuring the productivity of a developer or team by the number of story points completed over a quarter. This sizing of work is quite arbitrary and any obvious methods of sizing this like lines of code don't really work (although tech leaders asking for lines of code completed by each developer is not unheard of)

Since the task sizing is arbitrary there is no way to objectively measure productivity. Teams have an incentive (and the wiggle room) to inflate story points making it almost impossible to objectively measure productivity.

I think in the absence of any objective measures management has decided to anchor on the vibes of what productivity meant before the pandemic and wish to return to that. Teams like Cisco and some other firms that were fine for remote work before the pandemic are fine now too.