This week was full of interesting events. Finland joining NATO or the story of a starlet who may or may not have been involved in a ski accident or not-accident. But, we are in a quiet corner of the Internet here, so let’s track the news about Apple, famous for its products, making headway into becoming a service company.

Last week, Verge reported that Apple was launching the Apple Pay Later program. Apple also expanded the internal test of its “Buy Now, Pay Later” (BNPL) service to the company’s thousands of retail employees — likely indicating the last test steps before going public with the long-awaited feature, which will perhaps finally be released to everyone soon. So, I am going to be talking about Service Operations — on the heels of my mentioning, in passing, another such BNPL company, Klarna, in the post on Operations Lessons from Sweden.

To run the service, Apple created its own subsidiary, Apple Financing LLC, which will remain at an arm’s length from its main business. Apple Inc. hence will handle the lending itself for the new “buy now, pay later” offering, integrating itself into the financial services system. Apple’s BNPL plan was going to be released as a part of iOS 16, in September 2022, but then supposedly hit technical glitches in implementation.

The current plan allows customers to split into 4 installments all to be paid within 6 weeks, without any fees or interest. As a part of the plan, Apple users can apply for a loan within the Apple Wallet apparently “with no impact to their credit”, and then “pay later” mode will start appearing on their phones.

Apple has also been working with Goldman Sachs on offering a monthly payment plan that charges interest (which sounds very much like a credit card). Since 2019, Goldman Sachs has underwritten the Apple credit card.

Hence, Apple’s BNPL (buy now, pay later) plan is clearly not its first financial foray. Apple will run soft credit checks when a person applies for its BNPL service, loaning the buyers anywhere from $50 up to $1000. I wrote “apparently with no impact to their credit” earlier because the fine print does suggest that Apple will tighten credit to those who miss payments. That pretty much looks like a bank loan service to me.

Apple, A Bank?

So, is Apple a bank? No. For sure, Apple is still not a bank as of now (some definitional charter thingies are missing). It is however increasingly becoming a service company.

Since, the beginning of the pandemic, I have been wondering in my notes, about Apple's services plan and whether it is now finally a Service company. There is substantial evidence that iPhone as a product is maturing, and I typically mention it in the classes that I teach. One can see that Apple iPhone shipment volumes are flattening. Apple stopped releasing unit order data for iPhones in 2019, but we can still track shipment data.

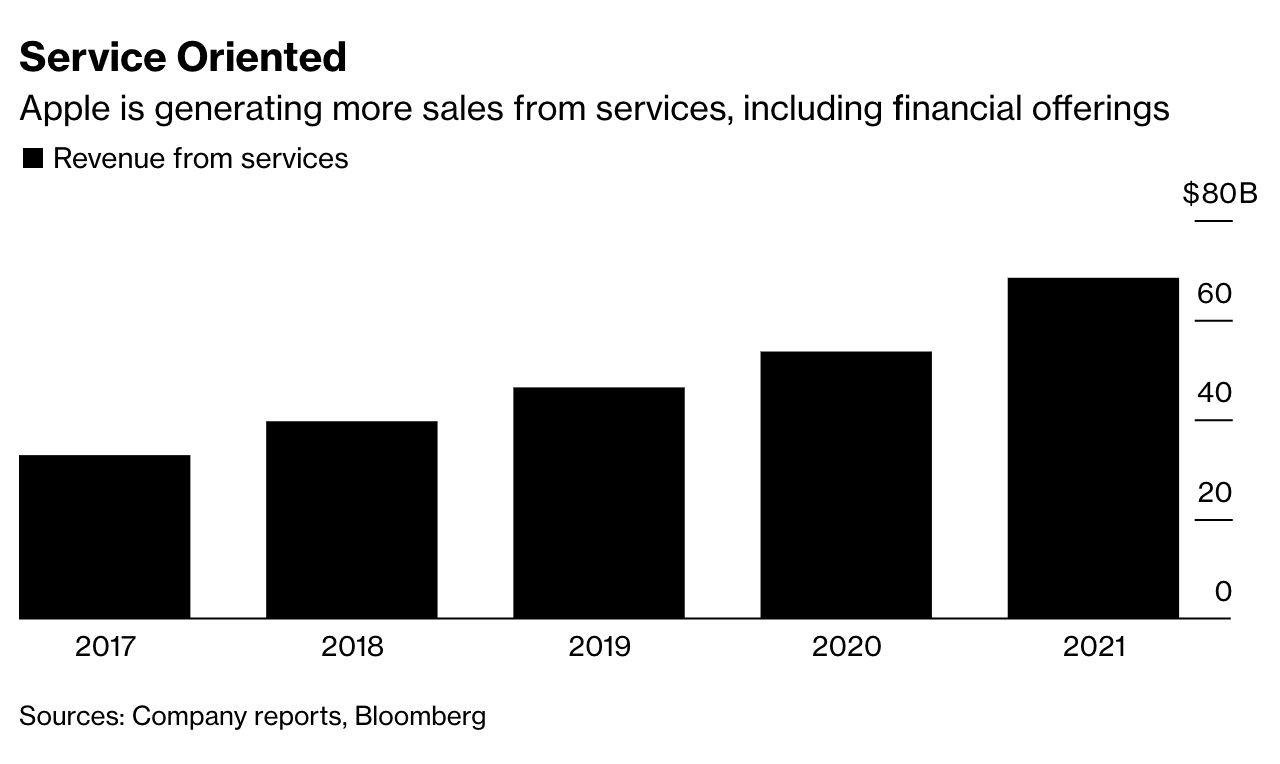

Eventually, even a company like Apple has to move to new greener pastures. The services business is that new pasture and for a while now, a substantial proportion of its revenues has been accruing from services. In fact, the evidence is very much strong, looking at the increasing revenues from services.

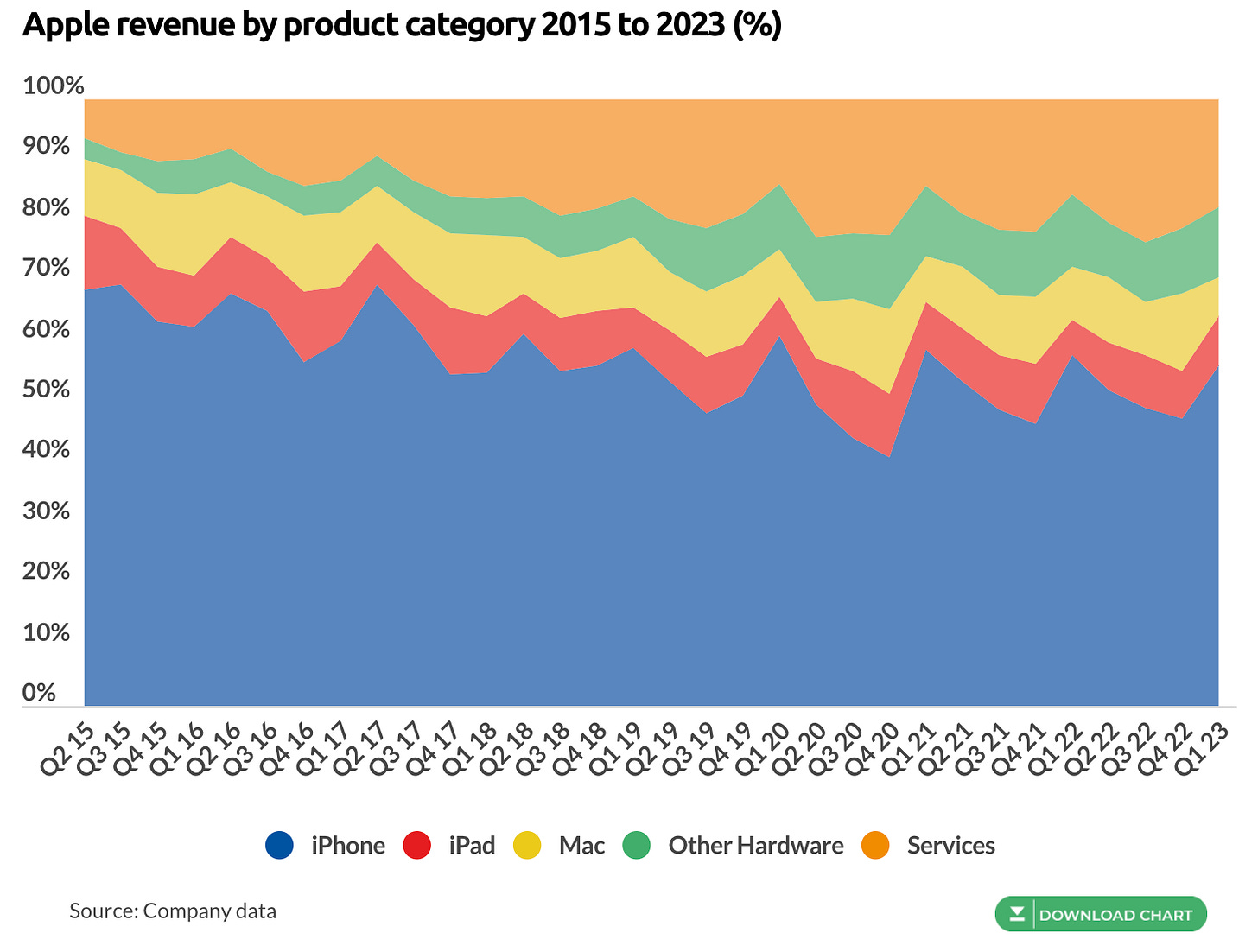

In 2021, Services had already accounted for >20% of their revenues — in fact, quite a bit more than Mac and iPad combined (9% and 7%). The pivot to services truly happened at the end of 2019. Services have steadily remained a sizeable proportion of their revenues since 2019.

As the figure above shows, over the last 7-8 years, the proportion of the revenues accrued by iPhone has been steadily decreasing, with an increase in Services and other hardware (which includes AirPods — those now ubiquitous accessories, and a stunning improvement in usability. No one thought much about them as being a revenue source when they came out).

Product-Service Bundles.

So many companies in the world are product-centric. We certainly think of Apple as a company that makes some cool products, and for years, Apple has been making high margins from those products that drove their business. We rarely think of them as a (Financial) Services Company.

Nevertheless, Apple’s move is a genuinely exciting case of a product-service bundle being taken in-house.

As the scope of customer-based analytics expands, we are seeing a reversal of old business practices. In nineties America, you could go to Best Buy or Circuit City to buy a TV. When you bought a TV, it was common for the retailer to sell an installment plan or even a maintenance plan. However, the maintenance plan was run by a third party. These ancillary services were considered expensive and therefore unbundled, spun out, and outsourced to third-party companies. (Similarly, we think of car loans with servicing handled by the banks for automotive companies).

Stores: Apple’s Best Recent Invention.

Apple Stores have been Apple’s most underrated “product” of the last decade. Apple stores have seen extraordinary sales per square foot (about $7200 per square foot in 2020). Even the pandemic only barely suppressed Apple’s Direct Sales (reducing them by only 10%). Apple's same-store sales dwarf the sales of the healthiest retail companies and even luxury brands like Tiffany’s. In 2021, Apple sold about 36% of its year-end revenue through its direct channels (on its website plus its stores).

Apple in many ways is a traditional supply chain. It outsources its production and manufactures a large number of products in China (now production has begun in India and Vietnam), and sells them in stores in North America. In inventory terms, Apple's Supply Chain is a “Make to Stock” system with high-cost inventory in stores and transit pipelines. It is worth remembering that Apple iPhones are expensive and held in high-priced real estate locations. So, the account receivables through quick payments are advantageous and help remedy the high inventory holding costs. In this respect, Apple has in fact had even better cash conversion cycles than Amazon.

Stores have been a boon in their direct sales strategy, and in reaching customers who otherwise do not visit Apple's website to buy products. (Apple started selling its products on Amazon only recently, in November 2018).

BNPL and Customer Centricity

I am not a big fan of the BNPL policy for the reasons that it incentivizes some customers to make poor decisions, prioritizing instant impulsive purchases over rational decisions. Needless to say, such customers have often been victims of salespeople armed with attractive installment payment offers with EMI and layaway plans, which have been used as predatory sales mechanisms, in getting customers to purchase items over their financial wherewithal. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) “identified several areas of risk of consumer harm,” a prevalence of “data harvesting” (though, who really doesn’t?) and states that BNPL is “engineered to encourage consumers to purchase more and borrow more.” On the flip side, it should be noted these customers have been risky bets for retailers who sell those products, as the collections of payments are unpredictable.

Control of these risks is why BNPL companies like Klarna and Affirm have been in vogue. Retailers love the BNPL companies, as the BNPL companies take the customers with low financial credit “off the retailer’s hands”, and carry those risks. BNPL companies in turn do better by balancing the risks of customers with poor payment history, with those “good” customers who have an unknown credit history, and those customers who are under-served by the traditional financial credit system.

Apple’s approach is interesting as it goes against “hire a third party” narrative, by taking on financial risk and dig deeper into the customer income funnel to understand the customer segments that have been traditionally priced out of the market by the high price of Apple products. Apple retail store employees, now reaching about 165,000 in 2022, are less well-paid than the engineers at Apple. I must admit paying off a purchase over six weeks does not sound like a tremendous financial relief that would make Apple’s plan attractive to many customers. While likely not the typical BNPL customers, the store employees are possibly the best customer segment (within their own employee pool) in terms of the likelihood of using BNPL to purchase expensive products.

It is truly about understanding who your customers are.

My colleague and co-author Pete Fader, has been evangelizing the concept of Customer Centricity valuing and understanding customers at a granular scale.

Fader: A requirement behind customer centricity is the ability to understand customers at a fairly granular level and to be able to identify the customers or the segments of customers who are valuable from the ones who aren’t. If you can’t sort out your customers — if you can’t look at them and know who is good and who is bad — then you can’t be customer centric. That’s step one.

Step two is having an operational ability as well as an organizational capability to be able to deliver different products and services to different kinds of customers. That’s tough to do.

All this goes to show that such customer relationship management is no longer a low-margin “hassle” but an important key to understanding their lifetime value. In fact, I expect more firms will take these processes in-house, as companies like Apple try to understand the position of each customer in their product-service ecosystem.