The Sentinel #27: Streaming and Bundling (Dis)Content.

Barbenheimer, Profit-Sharing, Strikes and Sturgeon's Law

Hi Friends,

The weird ways American culture pervades everything: It’s Barbie vs Oppenheimer day across the globe. Outlook Magazine in India published an article literally asking, “Barbenheimer Effect: Will The Release Of Barbie And Oppenheimer Come To The Rescue of The Indian Box Office?”

Several weeks back in discussing making decisions under incomplete information and Harry Truman (in the post Sentinel #17), I had briefly mentioned Barbie vs Oppenheimer and the duality of America. I have never caught anything first-day first show. I used to read trusty Roger Ebert when he was around before watching a film — miss him! — so I will wait for the more-informed folks I follow to tell me how the films turned out. But it seems an apt time to talk media business.

Back to Operations and Bundling

In light of ongoing discontent with the state of business (Hollywood strike), I focus on the tumultuous business model changes in the media industry. For readers who are not in the United States, the summary is as follows. The biggest union in Hollywood, SAG–AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild – American Federation of Television and Radio Artists) has gone on strike over an ongoing labor dispute with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) which has brought film and TV writing and production to a standstill. The conflict is mainly about how to split what’s called the Residuals — the customer proceeds that come from past shows between the studios and workers.

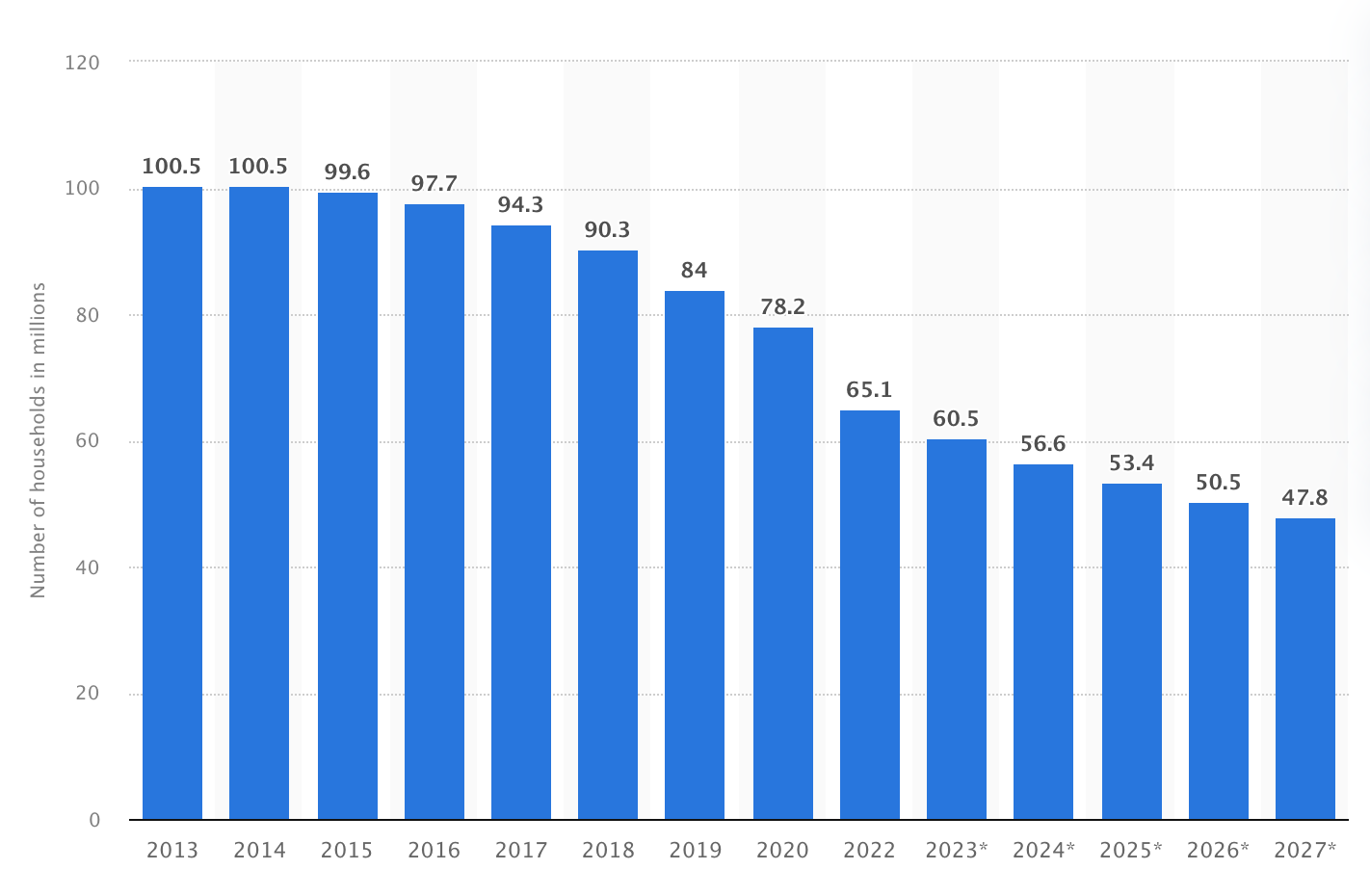

Let’s start with the landscape. As the figure below shows, compared to 2013, the biggest entertainment companies are STRUGGLING! (Or, are they really struggling?). What’s happening?

Here are the four informational issues in the decade that eventually culminated in the strike:

1. The Hidden Cost of Unbundling,

2. Inflation and Upfront Fixed Costs,

3. Volume (and Quality) of Content,

4. Profit Sharing vs. Revenue Sharing.

The Hidden Cost of Unbundling: FEEL the CHURN!

If you recall the dreamy days of 2013, it seemed that cable monopoly was dying, and streaming was the new thing that is going to save us all. Streaming will save the writers and creators: Better storytelling, better focus, and more niche programming. It was the “Golden Age of TV”.

So, a number of people in the United States “cut the cord”: you can see this in the data. More than 40% of people who had cable in 2012 stopped using cable services. The number of pay tv subscribers have substantially dropped over the years, and the pandemic accelerated the trend.

Bundling was great when it lasted. It was also sticky - as Cable was the one big thing. Bundling has its big benefits — as the reason it works is deceptively simple. Folks find parts of the bundle highly valuable and perceive that the rest of the items in the bundle package are thrown in for free. So, in the cable era, many were happy to pay $150 or more, to watch mostly sports and a couple of shows on AMC or Disney. They cross-subscribed a few ardent fans to niche channels like OLN or LMN - Ladies Movie Network, a channel that played movies of suburban housewives constantly in distress from clandestine nannies out to destroy their families and steal their man. Most importantly among the competitors like CNN, FOX, and MSNBC, it was a collaborative equilibrium — there was a stability of proceeds regardless of who was in the market lead — they all needed each other.

Linear TV was great for news and sports, and coverage of live events. Written content was traditionally programmed around linearity — ad breaks and all. This did not work much for films — you should be able to start and watch them whenever. So, technology like DVR and TiVO (remember?) were supposed to solve this.

Netflix was founded as a mailing intermediary that owned no content. Even though they sent DVDs home by mail, as the name suggested, founder Reed Hastings always saw it as something that would use the internet as a conduit. It is worth remembering, while unbundling linear TV, Netflix itself was a bundle of all-you-can-eat content buffet. So the ability to see all those shows and more for 19 bucks a month (later reduced when the mail business was shut down) was very cheap compared to the cable bundle.

In fact, during the same period, Netflix saw a stupendous growth from under 40 million subscribers in 2013 to more than 200 million subscribers in 2021. Naturally, the growth curve started flattening after some time (eventually every idea hits the diminishing marginal returns). Netflix had its first subscriber dip in 2022, leading to a lot of recent controls, including banning password sharing, adding fees for Ultra-HD streaming, restricting the number of devices, and a lower-priced tier with advertising (that was a no-no first).

Slowly, faced with this attractive opportunity in streaming, the collusive knife-edge equilibrium of cable unraveled, as participants one by one, HBO to Disney to NBC began chasing the goose that laid the golden egg.

Of course, this intensified the competition in the SVOD — Streaming Video on Demand — market even as the overall subscribers grew. Looking at the premium SVOD market — gross subscriber additions have expanded from 10 million, about 5 years back to about 40 million now.

Good news? Not really, as this becomes a game of shuffling more chairs on deck — as churn has also increased from 8 million customers in 2019 Q3 to about 30 million now. Last year, according to some industry data, churn is so high in streaming, that for every new subscriber added, they lost one customer — netting zero customers after all the investment.

The main hidden cost feature of subscriber service is churn. My own newsletter churn is about 0.3%. Surprisingly, the highest churn happens on the days when the newsletter goes out. It almost feels like I am reminding some folks to unsubscribe by producing new content!

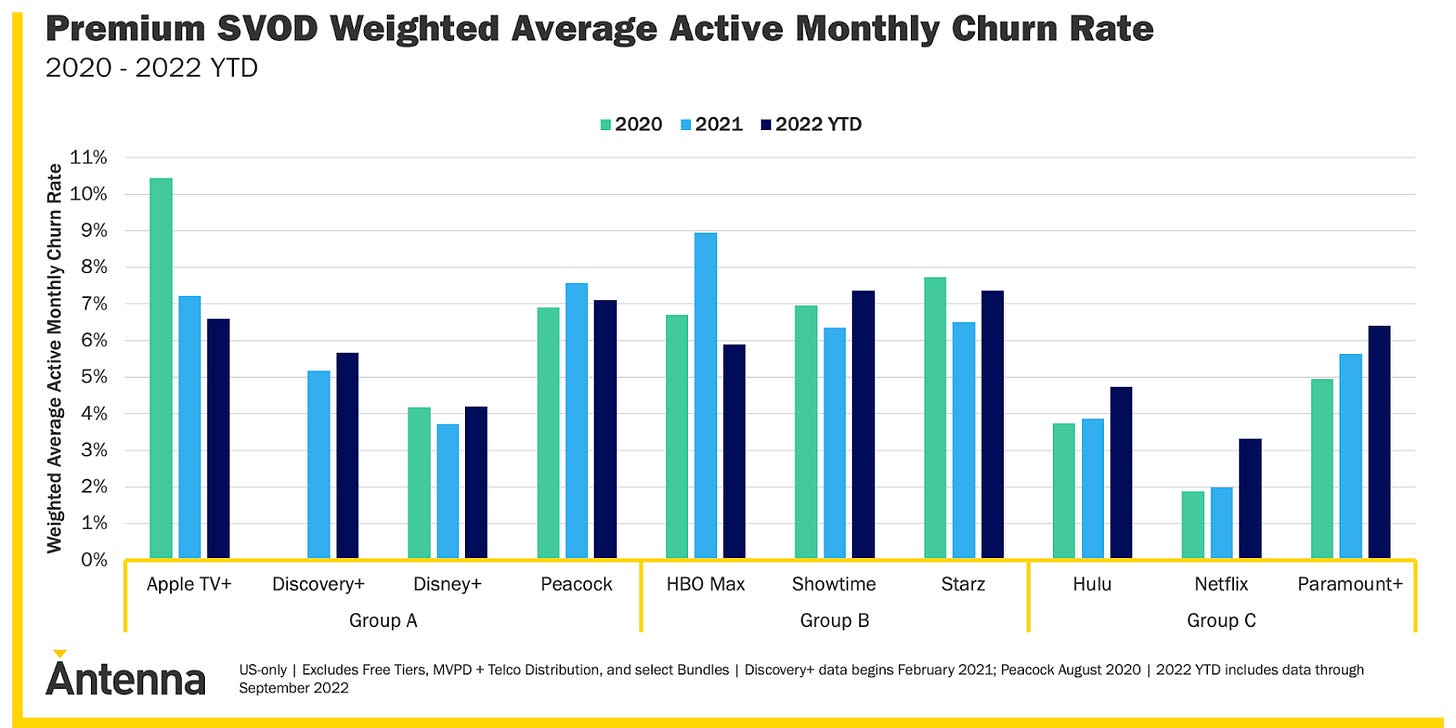

With increased competition, churn is a huge problem now. Despite the stickiness of the iOS ecosystem, Apple TV+ churns 7% of the customers. For every other competitor, the churn has only increased or stayed the same.

In 2017, the peak age of streaming, here’s Netflix CEO Reed Hastings:

“You get a show or a movie you’re really dying to watch, and you end up staying up late at night, so we actually compete with sleep,” … “And we’re winning!”

I am pretty sure that sleep is not the only competition now. Also, Netflix, while leading the market, is not winning. In fact, their churn has nearly doubled as per the data.

How does one stop the churn? As a media company, since everything is downstream from culture, you produce more content to keep up with cultural mores.

2. Content Escalation, Inflation, and Capital.

Content has seen explosive growth in recent years.

Netflix had the massive advantage (and foresight?) of being a first mover in a low-inflationary environment. Starting off as a pure intermediary, Netflix amassed enough cash flow, and investors to start producing content — Netflix now produces more than 50% of the content it streams.

Netflix is increasingly a media company than a tech company.

This transition to media-dom changes a few things. It moves the variable cost of technology upkeep and product management, to the fixed cost of content creation. In a low inflationary environment, Netflix was able to spend massively in creating its own shows (starting with House of Cards, and more shows like Stranger Things).

But for later entrants, Peacock, HBO, Showtime, Paramount, Disney, Amazon Video, and Apple — the cost of investment has been high and inflation has been an impediment. Over and above all, the returns are dwindling, as the businesses are all competing for the same subscribers.

One would think it is a great time to be a customer — low prices, heavy competition, and a plethora of content. Indeed, compared to the cable era, content is cheap and ubiquitous. The surplus has improved from a pricing perspective. Yet, paradoxically, the streaming revolution has not really led to an increase in the consumed supply of quality. This argument sounds strange.

3. GLUT in Quality

As a film aficionado, really just a fan, the last few years have been tiring because I have been resisting the notion that we live in a golden age of TV. In 1957 writing for Venture magazine, Theodore Sturgeon, an American science fiction writer, perhaps responding to the criticism about the low quality of science fiction, quipped — what’s now known as Sturgeon’s Law - “Ninety percent of everything is crap”.

Personally, I have found this maxim very helpful. Many days I wake up and think that ninety percent of my output is indeed CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) — my papers, this newsletter, my political views, past choices, and investments. The flip side of such destitute comportment is that it leaves me with a lingering sensation that to do better, I need to do more. Hope floats, and I try to be a better person by taking on new, exciting tasks.

Sounding like a curmudgeon, I find most of the streaming content in SVOD (subscription video on demand) to be terrible. I need more data in the newsletter to rigorously argue my point. In my view, extensive poor-quality content has invaded the streaming services — there is no other authentic stamp for a terrible film than saying it is a Netflix production.

You should not take my criticisms too seriously. I have never subscribed to HBO (or any of the hundreds of its avatars: HBO Max, HBO Go, HBO Now, etc) despite that, the two best shows I have watched in life are HBO shows — The Wire and Deadwood. But, let us look at some data.

I gathered the top-ranked shows on Netflix in the US in the past year (2022-2023) using public data from Netflix. I have seen *none* of these shows — so judge for yourself. Netflix Top Ranked Shows: Manifest, Virgin River (6 weeks), Outer Banks, All American, Clickbait, Squid Game, You, Narcos: Mexico, Tiger King, True Story, Money Heist, The Witcher, Cobra Kai, Cheer, Ozark, All of Us Are Dead, Inventing Anna, Worst Roommate Ever, Pieces of her, Bridgerton, The Ultimatum: Marry or Move on, Ozark, Stranger Things (7 weeks), Umbrella Academy, Dahmer, Sandman, The Crown, Wednesday, Ginny and Georgia, Manifest, New Amsterdam, The Night Agent, BEEF, Love is Blind, Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story.

I certainly cannot think of more than one show in the list of capturing or exceeding the quality of writing/artistry representative of the golden age of TV. (btw: I am delighted to wallow in campy content, and don’t think things have to be high-brow to be good). The real comparison set is the most watched cable or network TV shows, which include Game of Thrones, Breaking Bad, Sherlock, Big Bang Theory, and Walking Dead.

To be assured, a counterargument could be that the distribution of shows vs. views is highly dispersed: Many people are watching more shows and there is a high number of shows with substantial viewership. My hypothesis is against this, but certainly, more data is needed. I found an article by Benedict Evans who ran some back-of-the-envelope calculations and concluded that: “MrBeast has comparable hours of viewing across all his videos to a top 5 Netflix show.”

My argument is simply this: Very few shows are truly watched by a lot of subscribers, but these shows overwhelm our intellectual discourse. For instance, 35.3 million hours of Lincoln Lawyer were watched last week (roughly only 8m+ views assuming everyone watched the whole thing).

One thing to notice is that the top-selling shows remain in the top ten for an average of only 3.03 weeks (based on my calculations from the data on the top-10 shows in the United States).

This fact implies that there is also a huge churn in content. Shows run shorter periods of time, and with eyeballs dwindling very rapidly … which leads us to RESIDUALS.

So here are the culminating factors that lead to the SAG-AFTRA strike:

Very few of these shows are running in syndication as pay-tv has declined.

Shows don’t run for 13 (or 22) episodes like in linear TV, to develop dedicated long-term viewership.

Streaming shows typically drop out of the top 10 within two weeks.

Netflix and other content producers are constantly changing the next big thing every few weeks.

Capital to make new content has tightened under high inflation.

At this juncture, the pie is getting smaller. how do we share the pie? First, what is the pie?

4. PROFIT SHARING vs. Revenue sharing

I flagged the revenue sharing problems in Messi Revenue Sharing contracts in my post on “Messi Revenue Sharing Contracts”.

Platforms invariably provide multiple content offerings to consumers. They invariably have pressures and motivation to recommend options that have a higher return rate — just as a selfish salesperson directs consumers towards offerings that give him a better bonus. You have already seen these payout effects manifest in aesthetically terrible ways: Netflix often promotes its own crappy products (which is why I strictly avoid binge-watching), and Amazon Prime prominently shills its products on the TV screen and landing pages on websites. […] they may be incentivized to promote different content that has a better return. This will reduce the suppliers’ income flow.

Indeed, I was not surprised as such reporting differences happen due to conflicts of interest. Yet, it is still whimsical to hear a story about a movie that many people would recognize. I was a bit flummoxed to read a tweet by a famous actor, John Cusack.

Everyone remembers the picture. I guess John Hughes movies (Say Anything, Breakfast Club, and Sixteen Candles) are rewatched more than any of the streaming content — but it is simply hard to think that movie is still making a loss.

It is impossible to take a side on the strike without revealing some leanings. I think creators should earn more. Indeed, the whole idea of the Substack and creator economy indeed is premised on this aspiration.

Without a boombox, I can perhaps say the simplest, and the least controversial thing: revenues are easier to calculate and verify than profits. If two parties are agreeing on a contract on sharing proceeds, revenue sharing is often preferable to sharing profits, as it reduces two principal issues: Moral hazard (not putting in the effort to improve outcomes, after the fact) and operations forensics (profit verification by third parties).

I hope the next set of negotiations is based on Revenue data.