The Sentinel #30: Tariffs, Part I: American Experience

Farming and Electricity vs. Manufacturing and AI

Preamble: Tariffs are in the news. Nothing is more supply-chain-y than the tariffs. So, in service of my readers (half of whom live outside of the US) — the first piece of the essay, focusing on the American context. I will write about the second part on positioning this moment, and on where we go forward from here. Here is the first part.

In an iconic scene in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, a classic 80s movie directed by the fabulous John Hughes (who directed some great films on young people anxieties — Sixteen Candles and Breakfast Club), a dead-dull teacher is droning on about Tariffs and the Smoot-Hawley act. While he is talking, the suburban kid Bueller is playing hooky, goofing off with his girlfriend, and dancing on Chicago avenues to great 80s music. (Incidentally, Ben Stein, the actor playing the teacher, was a big trivia geek on the show, “Win Ben Stein’s Money.”)

Ben Stein: “In 1930, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, in an effort to alleviate the effects of the . . . Anyone? Anyone? . . . the Great Depression, passed the . . . Anyone? Anyone? . . . the Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act, which . . . Anyone? Raised or lowered? . . . raised tariffs. Did it work? Anyone? Anyone know the effects? . . . It did not work and the U.S. sank deeper into the Great Depression.”

So, the last time major tariffs happened, it is well known that the Great Depression followed. So how did we get here? How did no one care until it is too late?

As an operations professor, I want to talk supply chains and tariffs, but the world is sometimes more interested in Ghiblifying memes.

Tariffs and Nationalism

Tariffs are not new, and are often economic levies/taxes to ‘protect’ the interests of their in-group: culture, race, nation, creed, or whatever they hold dear. Nowadays, it is often associated with nationalism. I grew up in heavy tariff-ed India, often called as the License Raj, before 1991. Incidentally, US was also high tariff nation before it emerged as a global power in the early 20th century.

As one can see from the above picture, the current announced tariffs are comparable to or even higher than the rates introduced in the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930. By 1932, almost twenty-three trading partners of the US, imposed counter-tariffs. Additionally, some nations retaliated by shifting their preferences. For instance, Canada reduced their tariffs on the British Empire.

As you can see, there was a disastrous drop in equity markets after the Smoot-Hawley tariff act. It is helpful to make a note that international trade is now multiple times more interlinked than the 1930s. The equities showed improvement over time, after the passing of Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, 1934, under President FDR.

To fully understand American tariffs (and the last President who signed it off), we need to begin at the top of the century: a quick look at 1900s China and The Boxer Rebellion.

Kungfu Nationalism

The Boxer Rebellion is still controversial. In the official CCP view, it was a patriotic but poorly organized uprising of the peasants in North China (Shandong Province) to drive out all the globalist foreigners and the Christian missionaries destroying the country. Others view it as an ugly xenophobic strategy employed by Dowager Cixi to strengthen her grip on the Qing throne. It was, for sure, a nationalistic movement.

We know two things for sure: “Boxer” is a mistaken term that has lived on due to the British who did not know Kung Fu. In reality, the Boxers called themselves Yihequan (义和拳) which translates to a very cool sounding name: The Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists. So cool that at least some members believed that their martial arts made them immune to bullets, which would bounce off their bodies.1

Secondly, the uprising was violent and resulted in more than 100,000 deaths (mostly Chinese civilians). My trusty old copy of Jonathan Spence’s The Search for Modern China notes on the kind of attacks that:2

[…] families retreated into a defensive area […] hastily defended with makeshift barricades of furniture, sandbags, timber and mattresses.3

In the chaos of the attack on the port of Tianjin (outside of Beijing), a 26-year old American man arrived along with his newly-wed wife, Lou. His name was Herbert Hoover. He had just received a plum-promotion to be the chief engineer in China for a British company called Bewick, Moering & Co. (We love engineering in this blog!). Herbert jumped in to organize the food supply network and water purification in Tianjin.

Later, an alliance of 8-nations, Austria-Hungary, Germany, Japan, Russia, Britain, France, Italy, and the United States (which was engaging in naval combat in China for the first time), defeated the Boxer rebellion. This defeat fomented the downfall of Imperial China. The Qing Dynasty agreed to pay an indemnity of 450 million taels (a staggering sum that was twice the Qing annual tax income).

Hoover: Operations Engineer, Ops Consultant and Humanitarian

In the aftermath, Herbert Hoover helped successfully reorganize the company and was offered a junior partnership in the firm.

Soon, the orphaned son of a Midwestern blacksmith from West Branch, Iowa with Quaker upbringing, a man who was part of the first graduating class of a new university called the Stanford University, had, by 1914, built a personal fortune in business and was managing the multinational business in London. (Not before spending five years across the globe as itinerant traveler, before aircrafts were invented). But wait, he does better!

In the first weeks of the Great War (WWI), Hoover organized more than 100,000 weary and stranded Americans to return home.

Thankful, the Ambassador to Great Britain, Walter Page, tapped Hoover as the director of Commission for Relief in Belgium, which was suffering from German Occupation and British Naval Blockade.

Over those years, CRB (Commission for Relief in Belgium) under Hoover, fed and saved more than 9 million people in Belgium and France. The CRB purchased rice from Burma, corn from Argentina, beans from China, and wheat, meat, and fats from the United States, and worked with 40,000 Belgian volunteers to deliver to more than 2500 villages and towns.

As described in a diary, there was a lot of what we call E-commerce Operations (source: National Archives):

When the flour is finally milled, the real work of distribution begins. Sacks must be provided and kept in rotation. The exact quantity of flour required by a given Commune for a given period must be ascertained. Shipments by canal or rail or tram or wagon must be made to every Commune dependent upon the mill. Boats and cars and horses must be obtained and oil must be supplied for engines and fodder for horses. When the flour has reached the Local Committee it must be carefully distributed among the bakers in accordance with the needs of each. Baking involves yeast, and the maintenance of yeast factories, and the disposal of byproducts, and questions of hygiene and a dozen other minor matters. When the bread is baked it must be distributed to the population by any one of a dazes methods which guarantee an absolutely equitable distribution, each man, woman and child getting the varying ration to which he is entitled, paying for it if he can afford it, and getting it free if he can't. All this involves financial problems, and bookkeeping, and checking and inspection, all along the line; and the whole process to the tune of endless bickering with German authorities high and low, and endless discussions with a thousand Belgian committees.

If you think about it, this is kind of amazing. So, let’s recap Hoover’s life before he became President.

Hoover was a religious person, hard working, highly successful in the field of business, multi-lingual (Hoover learned Mandarin!), who spent time in service abroad, held high-level political positions, and devised plans to bring aid/food/healthcare to millions. A man of character, not an ideologue, and free of corrupt scandals. As someone noted, sounds a bit like Mitt Romney. If American people had known what was to transpire in 1928, they would have still elected Hoover.

The Great Depression did not happen overnight. Hoover was careful, fastidious and deferential to Congressional powers — the Smoot-Hawley bill was vociferously debated in Congress for several months and eventually passed raising tariffs over 2000 items — the Great Depression occurred after a democratic (and political) process. According to Whyte’s biography,4 Hoover got boxed in due to the politics of the process, even though he had in private notes described the bill as extortionate and obnoxious. What is not debated, even among causal arguments, is that the effects were disastrous.

1920s vs 2020s: Two Parallels.

Sometimes, history repeats itself, but sometimes, it sings an entirely different tune. Contrary to the 1930s, it is clear that this time, congressional process is entirely absent. So, how do we think about how we are at the present moment, structurally? I want to highlight two comparisons for you to think about, as I link and expand upon them in the next essay.

1. Manufacturing is the New Farming.

In the 1920s, farming was an industry that was moving towards industrialization from homesteading families. As the European agricultural production recovered after WWI, American farming lost its market. In the absence of Tariff protections offered to other new industries, American farmers were seeing stiff competition and low productivity. So to even out the foreign and domestic production costs, the Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act (1913) raised tariffs for farming. This act was a precursor to the Smoot-Hawley Act, that wanted such tariff “benefits/protections” to other sectors.

In 2020s, manufacturing (think of auto manufacturing) in the US faces a similar dilemma: the cost of production domestically is more expensive (and productivity lower) than abroad. In the current politics, manufacturing cost differential is being as used as a cudgel to build tariffs, even though the biggest constraint to manufacturing is the Labor Supply Problem in the US.

2. AI is the new Electricity.

In the 1920s, the United States was electrified at rapid pace. At the beginning of the decade, 20% of the houses were electrified. By 1930, about 90% of the urban and (non-farm) rural homes were electrified.5 But only one in ten farms were electrified, as electricity threatened farm jobs. The resulting productivity benefits through electrification were hence lopsided.

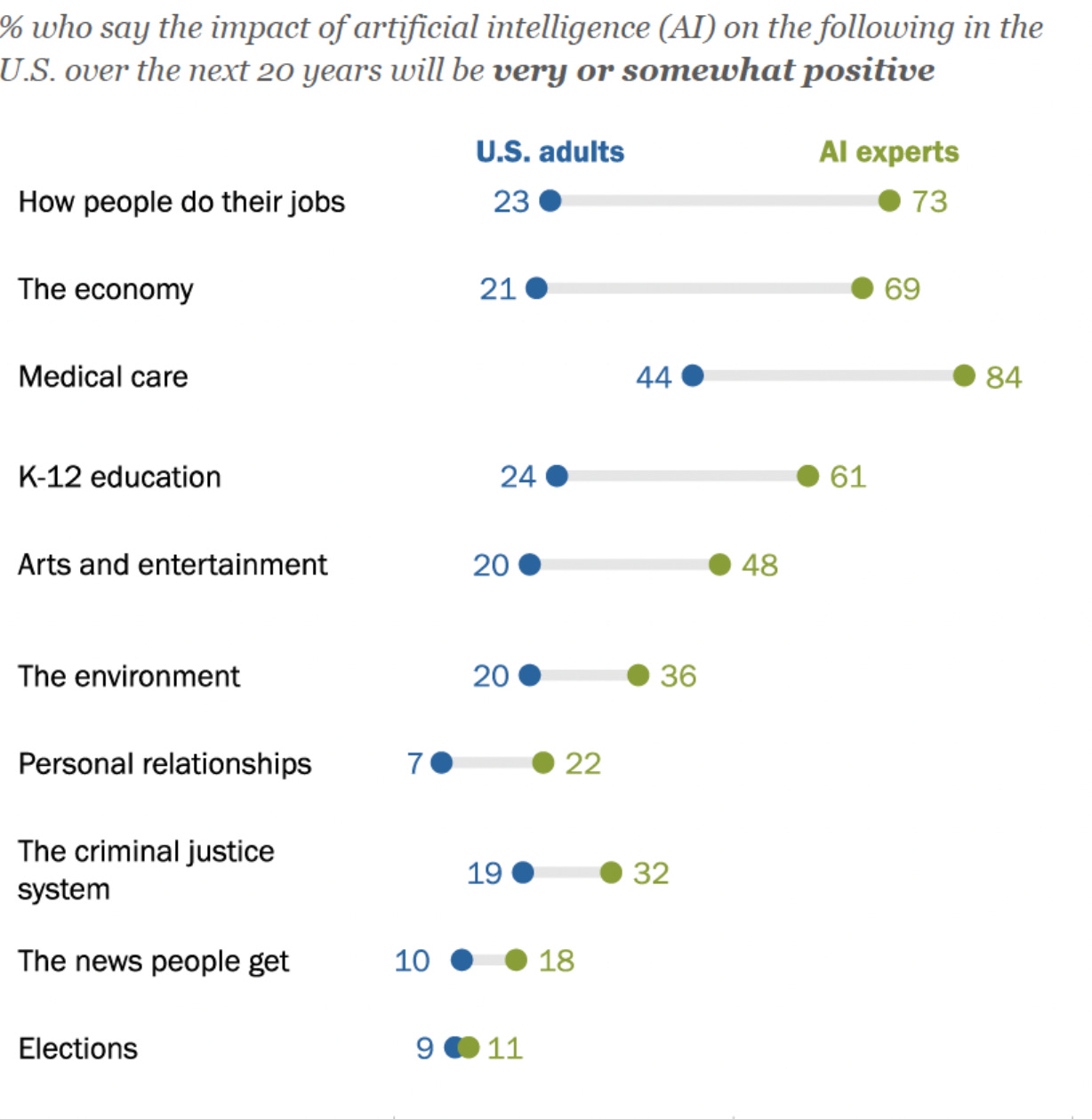

Right now, almost 90% of the Americans have access to smartphones. Now, what proportion of US adults think that AI on their devices will help them (compared to experts)? It is dismally low, and that is part of our worries.

The second biggest problem with the current tariff action is that it is backward-looking about physical goods and completely ignores services. I don’t think most of us are going to be working in factories, just like how most people were not working in farms. So, how do we think about the 2020s?

More in Part 2…

A martial arts film by a famous Hong Kong martial arts director Cheh Chang called Boxer Rebellion (1976) has the following blurb: “In the year 1900, China was being invaded by an eight nation alliance. Meanwhile, three martial artists join a xenophobic kung fu cult, with a large following, whose leader claims that he can teach his followers how to become bulletproof.”

This kind of Alamo standoff was pictured in a film called 55 Days at Peking (1963), starring Charlton Heston and Ava Gardner. It is a soppy film I saw only glimpses of.

Jonathan D Spence. The Search for Modern China. Chapter: New Tensions in the Late Qing.

Hoover: An Extraordinary Life in Extraordinary Times by Kenneth Whyte.

The amazing footnote to this footnote, is that Kenneth Whyte is a Canadian. This delightful book gives us an essential, highly recommended, neutral view of the President who presided over the most consequential economic event of the 20th century.

Richmond Fed. Electrifying Rural America. Econ Focus, First Quarter 2020.

Glad to know Mr. Hoover's experience in China and operations! Looking forward to the part II.