Using my notes made during the pandemic, I examine three big changes that covid-19 had caused. I wrote about how covid destroyed my friendships and help me rediscover appreciation for good friendships.

In this essay, I focus on Gender & Workforce, mostly trying to make sense from labor force data using Bullwhip, Claudia Goldin’s research on greedy work, and new cultural explorations in recent books, and why Satya Nadella is such a great role model.

In the US, there has been a lot of moral panic and a lot of hand wringing about what to do with the lost men in the current world. Part of the argument is that cultural expectations and norms have been shattered and men are now astray. There is both a small kernel of truth and a layer of overstatements to these kind of fraught analysis. These low expectations are not new! We can go back all the way to the 50s.

Daphne: […] Osgood, I'm gonna level with you. We can't get married at all.

Osgood: Why not?

Daphne: Well, in the first place, I'm not a natural blonde.

Osgood: Doesn't matter.

Daphne: I smoke! I smoke all the time!

Osgood: I don't care.

Daphne: Well, I have a terrible past. For three years now, I've been living with a saxophone player.

Osgood: I forgive you.

Daphne: [Tragically] I can never have children!

Osgood: We can adopt some.

Daphne/Jerry: But you don't understand, Osgood! [Whips off his wig, exasperated, and changes to a manly voice] Uhhh, I'm a man!

Osgood: [Looks at him then turns back, unperturbed] Well, nobody's perfect!

Age, Gender and Covid

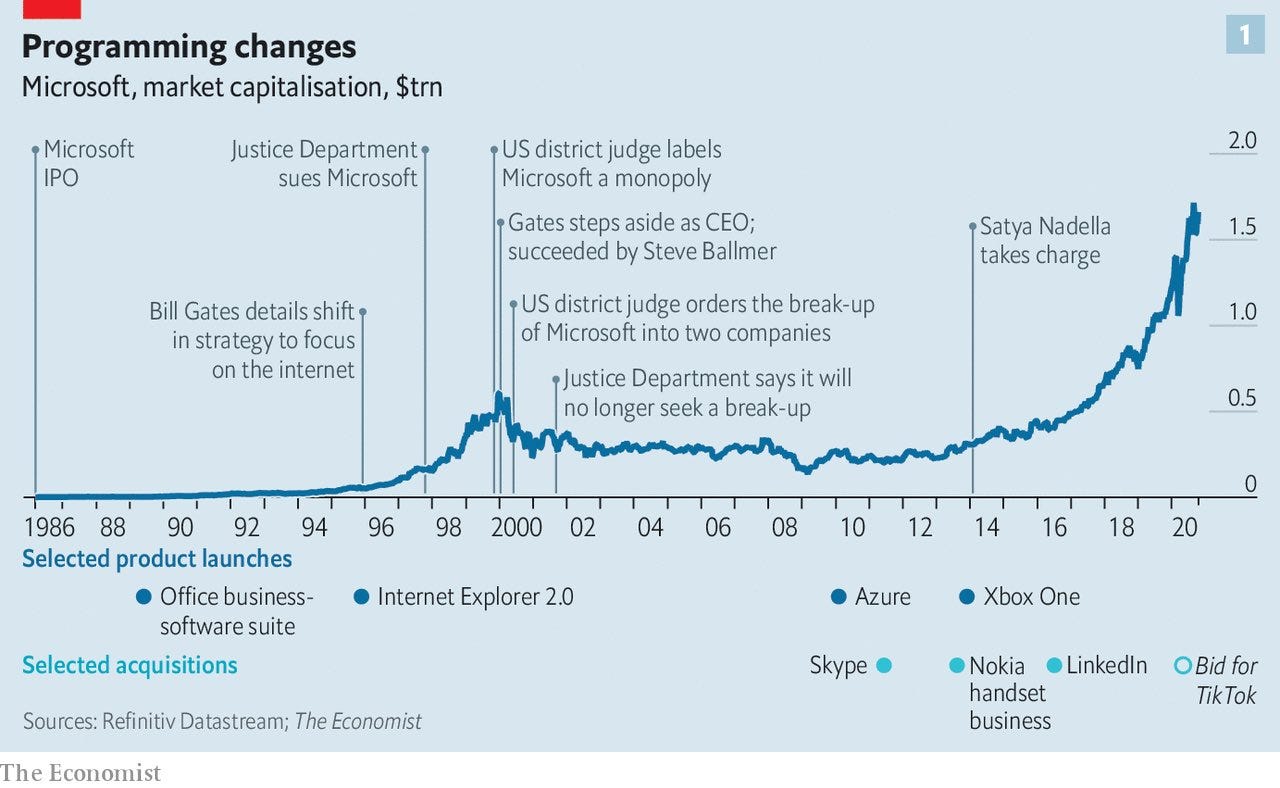

In the United States, there has been a wide difference in which age groups returned to work after COVID. 1 It is clear that older people in age group (55 and older) are not back into the workforce. There are likely two reasons why this gap has happened: First, the tragic. Covid death toll on the older age group was higher than other age groups. Second, Real Estate. The richer end of the older workforce are no-longer strapped with mortgages, and their houses have accumulated in value, allowing them to retire from workforce.

It is also patent from the graph that the young population haven’t returned at the same rates as the “working age” population. There is more to say on this. I was young once! (As David Cameron said to Tony Blair in the UK parliament, “He was the future, once”).

For now, let’s look a bit deeper into the age group that I squarely belong to, the “working age” population between ages 25 to 54. (Orange in the above chart). I used to always half-jokingly say that the covid vaccine priority schemes shouldn’t have been designed to decrease in age. They should have been allotted first for population above 55 (we save their lives), and then to the population under 25 (we save their social lives) — and then the 25-55 age group, who are “happy” to work from home until the pandemic subsided.

When we look at the chart split by gender, it is clear that a higher proportion of women have returned to the labor-force compared to men. Why? What’s happening?

Where are the men? Before we do that let’s take a look why we expect this kind of variations to be transitory.

Bullwhip, Men and Vendor Managed Inventory.

In my research field of Operations, we often love to analyze people as inventories. During the pandemic years, everywhere in the news, there has been reports of shortages and stock-outs of all kinds of things: bobas, toilet papers, kettle bells, bicycles, gypsum, used cars, and now even, eggs! All this while, there has been a shortage of people too! Truck drivers, school bus drivers, manufacturing workers have been hard to find. Bullwhip in the supply chain persisted as things slowly got back to normal after the pandemic shock.

One case study that we teach on bullwhip effect, is on a famous Italian Pasta maker, Barilla. Barilla built a supply chain system to improve visibility into their buyers’ inventory, to reduce the supply chain costs. (Under the program, instead of looking into the warehouse to decide how to restock, you look into your buyer’s shelf and decide what to order to and when to order based on their needs). In the figure below (an old-school figure resembling a printout from a fax machine), there is a schematic of what happened in a supply chain, when the inventory levels readjusted based on their VMI (vendor managed inventory) program.

Ideally, this intervention should reduce inventories in a supply chain. However, as you can see in the figure, for a while, inventory goes up! This is the nature of transition phase due to any large change. There is too much inventory of some products on the buyer’s shelves. As a result, as a company you have to be patient, and wait for the inventory to draw down slowly before new system begins.

You can see that covid workforce charts are mirror images of these kind of inventory charts: Covid suppressed the workforce participation, which will rise to a new level over time as people return to workforce, and may not necessarily return to pre-pandemic levels.

The “Middle” of the Middle age crisis.

Let’s take an even closer look into the working population segment between ages 25-54.

The chart shows that men between the ages of 35-44 during the period returned to work at lower rates than the older group in the segment (45-54) and the younger segment (25-34) which was back almost pre-pandemic levels. Looking at a similar chart for women shows not much gap between the age groups.

As in my case, the pandemic gave an opportunity to reconsider how we work; and what kind of work was meaningful with many to reconsider the quality of jobs and life decisions. It was an opportune time to people in the work force to figure things out.

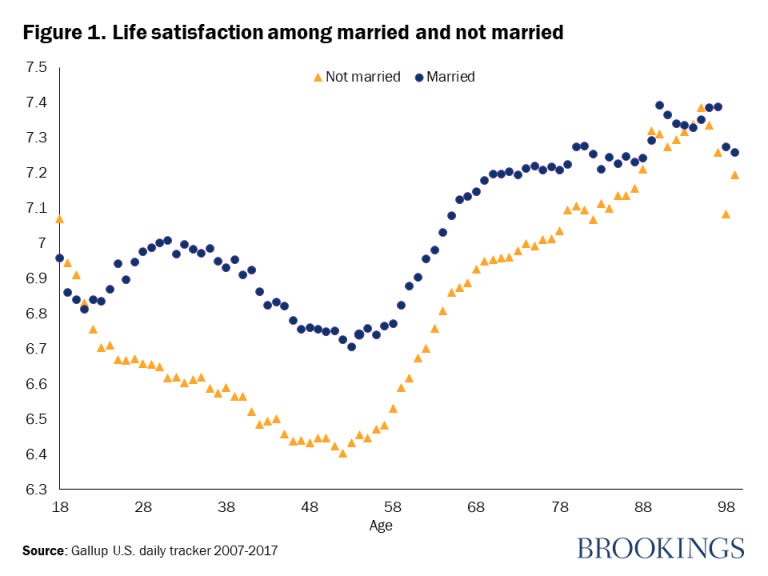

May be it is simply that when people are in their high 30s and mid 40s, they are spiraling down the sadness curve of middle age crisis (as shown in the Brookings Study). COVID was a perfect vice clamping this group in the middle: children with schools shuttered and parents at pandemic risk. Having squarely belonged in age group in 2020, this was pretty much an amplified worry everyday.

Now that we are in 2023, why is there still a big loss? One possible explanation is long covid. Indeed, some data points to that. However, I cannot speak to this with any expertise. Nevertheless, this observation does not quite explain the gender gap in how people have returned to work.

Dual Careers and Greedy Work:

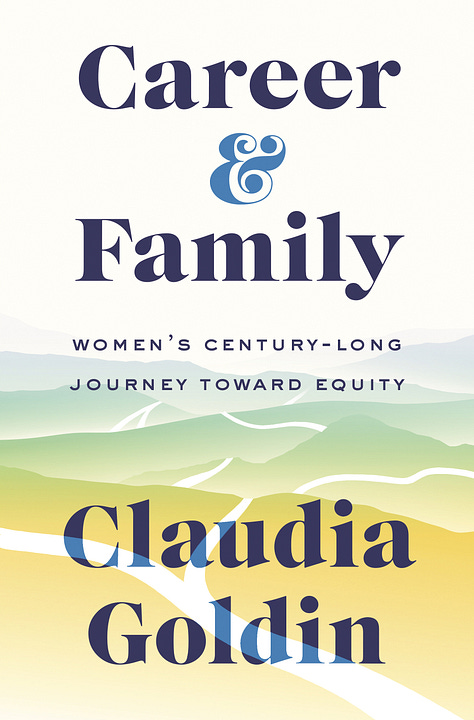

One of the most fundamental concepts due to Claudia Goldin’s work on Career and Family, is the emergence of the idea of greedy work. Focusing on dual career couples, she asks a fundamental question:

Why can’t dual-career families share the joys and duties of parenting equally?

One of the interesting findings is inequity is strictly not a gender inequity but a structural inequality. The main reason is the appeal of “higher pay” from “greedy work”. Greedy work is the work of the employee who is willing to put in all kinds of extended hours at all kinds of time. Not only the people who put in “greedy work” get longer hours of pay, they are also rewarded with higher pay per hour, promotions and get further attractive greedy work. The person who is bound by home responsibilities takes the hit. This is true in academic careers as well.

These differences in greedy work need not be gender-based, but often are. Successful women academics often credit their spouses who take care of the household. The basic sad truth to the finding — There is perhaps no way to find a static 50-50 split without sacrificing the overall pie, because a 50-50 split would require both to avoid greedy work.

Covid took a sledgehammer to Greedy work. It was mostly men who were engaged in greedy work before the pandemic. When business travel ended and remote work began, more and more men have reconsidered the real hidden costs of greedy work (health, loss of time with family, etc.). While, it is not clear if there an increased household work sharing from men, there is some preliminary data in support.

Family Men and “STEM” Worship

One of the biggest gaps that we see is that people (both men and women) without degrees have struggled to return to the workforce. While the nature of greedy work explains some of the gap between men and women but it does not truly explain the gap created by educational differences.

My hunch is here that white collars jobs have returned to work due to excellent WFH (work from home) flexibility but that blue collar jobs has lagged behind. In addition, for men entering labor force into specific careers has been a struggle. Perhaps, this is where the explanations are cultural. It has been argued that males have no good role models.

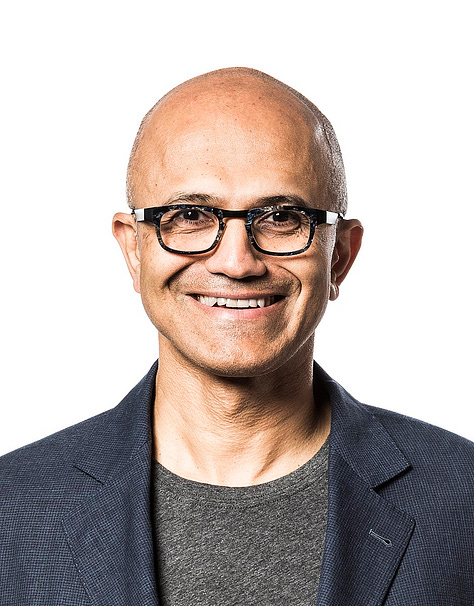

I am hardly impressed with the argument that there are no good male role models. Case in Point: Instead of following role models like Satya Nadella, the itinerant hero worshipers seem to be looking everywhere else, nowadays. The Valley is all wrong in elevating the wrong type of role models, including an assortment of workplace harassers, terrible fathers, culture warriors, dilettantes, and argumentative obsessives.

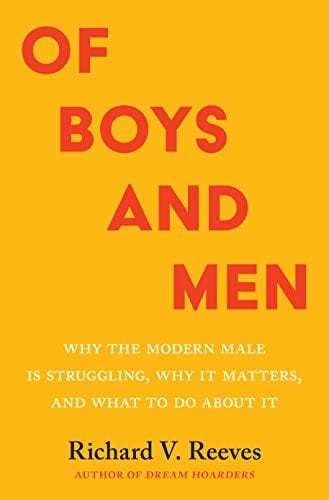

On this note, I have recently been reading Richard Reeves’ Of Boys and Men, which seems to argue the absence of role models with more nuance. Reeves argues that improving the conditions of both men and women in workforce should not be viewed as zero sum game, which is something worth enunciating. Although this topic is full of minefields, Reeves does not get into culture wars. Yet, one of the weaknesses is that, for better or for worse, his cultural arguments have been narrowly about the US society, and seem to hold little value or lessons elsewhere in the world.

There are two specific ideas that are lacking in the United States workforce that I want to deal with future essays: Rediscovering Value in Manufacturing, and Creating resilient “non-STEM” jobs (nursing, school education).

Do write me. I have been some getting some mail and suggestions, which I look forward to sharing here. Through one such recommendation, I plan to a begin a series, Friday Film Features, a short paragraph at the end of newsletter, focusing on foreign films.

Finally, if you love what you are reading — please subscribe and share. It is gratifying to see that I am getting far more “reads” than subscribers. I totally understand exploring, I am slow adopter myself. Please do subscribe, when you subscribe, I find it meaningfully supportive. Thanks!

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/02/business/economy/job-market-middle-aged-men.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/12/business/economy/labor-participation-covid.html

Great post! Some like it hot is one of my absolute favorite comedies, so many great throwaway lines. Up there along with Young Frankenstein for me.

Keep hearing about Microsoft under Nadella doing well because it's more "developer friendly", wonder if it's the same as internal service quality of Service Profit Chain, or if there's more to it. Looking forward to your next post and the Friday Film series.