I want to talk about groceries! (Who says it’s boring?) Specifically, why grocery e-commerce is so hard! Let’s start with one of the earliest examples of supermarkets in films — an excellent film noir, Double Indemnity (1944).

I ❤️ Reader Mail.

Before I head into the cold storage of grocery logic, I wanted to highlight a warm feature that I enjoy about writing on Substack. There is already a good network of substack readers and early supporters for this newsletter. Every week, I have been getting a few emails. Even before I can respond to them, when I read the emails, I melt, like… butter in Lord Krishna’s hands. Your support is providence that feeds this newsletter.

Just in the last week, I have heard from a working mom in Calgary, a schoolteacher in rural Pennsylvania, a high schooler in Texas, an undergraduate student in India, and not to mention, an investor friend whose writing and intellect I have admired for many years! Please write to me, or leave your comments at the end of the post. If you like what you read, please share.

One past student of mine, A., who has been working in retail for several years, reached out after reading, “How long will Amazon Retail last?”. He pointed out how the firms now surviving from the 1920s are all grocery stores, which led me down this path.

Stores are NOT Dead!

How is it that grocery stores thrive while apparel retail stores fail? Especially, if groceries are a low-margin business and if e-commerce allows for more “scale” and “efficiency” than brick-and-mortar stores, we should not see grocery stores thriving and grocery e-commerce struggling. Despite the acceleration of e-commerce, brick-and-mortar store as a retail model is not gone. Malls are dying for sure, but online groceries are faced with many challenges. A quick look at the margins of the grocery business confirms this idea.

It is apparent that the in-store grocery model is profitable. Both the internet models — delivery and “click-and-collect” — do worse than brick and mortar “in-store” model. Worse, delivery or service fees don’t seem to recoup the losses. Moreover, a “halfway” strategy like “click and collect” (customer orders online and picks it up from the store) does better than direct delivery. But, the most important takeaway from the chart, is that it shows how thin the grocery margins are.

So much so, that Amazon, which “purportedly” killed the brick & mortar model now wants to expand stores. Andy Jassy wants to “go big on stores”: Amazon bought Whole Foods five years back — but it has not made a big dent in the 1.6 trillion grocery market in the US. Due to the tightening Tech market, investment in Amazon Fresh has slowed down. Only about 40 Amazon Fresh stores exist. (I had previously argued how AWS feeds the retail business). Amazon Go still has the vibes of an experimental venture, and its “four-star” stores are now closed.

Meanwhile, the Amazon Fresh delivery-only business has gained only limited traction, with Amazon instituting a $9.95 delivery fee in the US for orders under $50. Jassy said he was “optimistic” about its online grocery business, but acknowledged that “people want to actually touch and feel” food before buying.” (source: FT)

Why has it been hard to integrate the delivery business with the grocery business? The pandemic was something that was supposed to accelerate the move of groceries into e-commerce and delivery. Yet, that hasn’t happened. Why is this?

Sometimes, the cheapest way to deliver products to customers is to get them to the store.

COVID was just a (big?) blip in Grocery Fundamentals.

First, let’s eliminate covid as a demand-side story. It looks pandemic created a Dirac-delta-type impulse function on steady grocery demand.

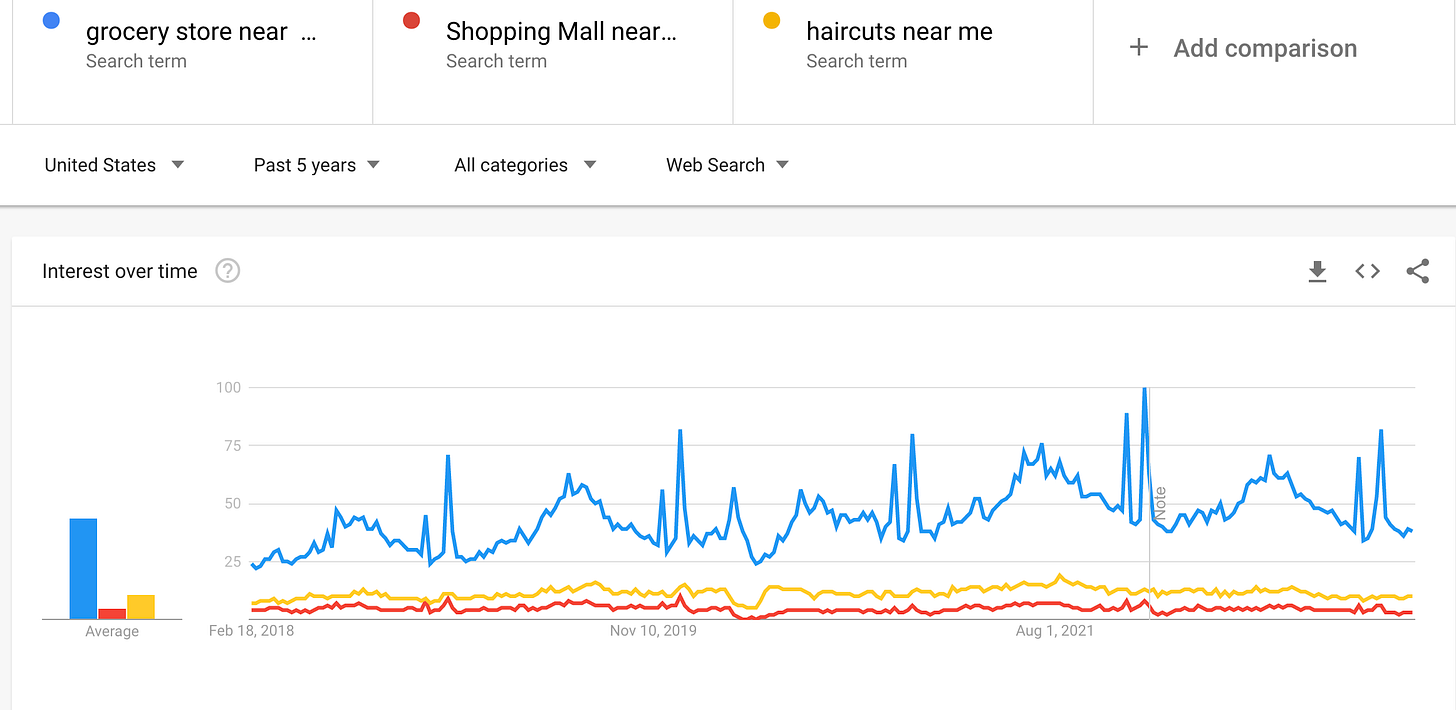

Not only did the search for grocery delivery (shown in blue) die out within months of March 2020 in the United States, but it has also fallen to pre-pandemic levels. In fact, fallen way below the search for “grocery store near me” search in the US (shown in red).

I don’t want to generalize the facts based on data from the US data alone. Grocery delivery can subsist as a profitable model in some parts of the US and many parts of the world. However, the success depends on how the highly educated/wealthy sections of society which like the convenience of grocery delivery convenience perceive the costs of going to the store. If they find their “travel costs” prohibitive (the last-mile cost is high for them), and if there is an excess availability of cheap labor, delivery models can thrive — even without some efficiencies. In the Philippines, India, the UK, and Malaysia — there is high interest in grocery delivery, due to a combination of the above reasons.

So, I re-visit the three rules in the picture to understand groceries as a business.

Three Rules of Grocery Business

Rule 1: The Hummingbird Rule: Perishability and Turns.

If the margins are so thin, why do grocers stay in business?

The usual answer that you will find on the internet search is volume. Grocers sell so much that volume makes up for the margins. This is true. But, only partly true. Worse, it is a tempting assessment as the volume gets confused with the scale. If you have scale, you will hear, you will automatically have volumes (which will in turn help with margins). Hence, you come across enormous investments in “scale” that will reap the profits.

But the secret sauce to successful margins in this business is TURNS (which is a combination of speed and efficiency). Inventory Turns is another word for how often a firm cycles through its inventory in a year. Suppose an independent grocer “Tim” who sells buys and sells bananas every day. Suppose he holds a day’s inventory on average. Tim’s Inventory turns = 365. (I am doing very “rough” math on average inventory here for illustrative ease). Compare this with another grocer “Tom” —who holds two days of inventory. Tom’s turns = 182.5, which is slower than “Tim”.

A classic paper by Gaur et al (2005)1 shows you can afford to be “slow” in brick-and-mortar business if the margins are high. In other words, Brick and Mortar businesses can only sell items that are “above” the pink curve. As an example, a jeweler like Tiffany has a sizeable gross margin and can afford to be “slow” — i.e., they can carry inventory even at high holding costs for a long period before it is sold.

On the other hand, Groceries have low margins (marked in RED in the figure). In order to be profitable, the grocer has to turn inventory much faster! Worse, the grocer has to stay “small” and stay “nimble”

The rule again is to be a hummingbird. Constantly moving. Staying small to stay alive.

Improvement in Inventory turns can be done in two ways: Limiting Inventory (limiting scale!) & Reducing waste. Don’t carry too much inventory at a time; Order and refill frequently. Second, don’t let anything perish. Sell it before it goes bad. Limit yourself to inventory that you can guarantee to sell before it perishes.

Let’s go back to our example grocer, Tim, who carries an average inventory worth a day’s sales. If 20% of his bananas go to waste every day, his turns are reduced by 20% as he sells less. In fact, his turns = 0.8*365= 292.

So managing perishability is a big problem: Customers love LIFO (Last In First Out) — buying the freshest milk bottle in the store, whereas the stores love FIFO (First In First Out). Every customer, who has reached across the frozen food aisle, to pick up the milk bottle way in the back that has the most recent date, is playing out the conflict.

Suppose, you were a customer ordering groceries on delivery. How sure are you that your picker (if he is a third party or a store picker), is picking the freshest banana?

Rule 2: Food is Well Understood but Weird: Basket Size and Assortment.

A typical American visits the grocery store a few times a month. 28% of people go to the grocery store less than 4 times a month, 38% of people go to the grocery store less than 4 to 5 times a month, and 34% of people go to the grocery store 6 or more times a month (Drive Research, 2022).2

So the basket size is fairly small for customers. If every customer had a large basket to buy, the Costco model would work perfectly — and delivery models could work well as well — because shipping costs would be a small proportion of the total purchase order.

Unfortunately, this is not the case — basket sizes are small, and they also vary highly between the customers. They also have the way complementarity problem of supply chain assemblies. One missing chip and there is no car. Grocery orders can be a bit like that.

Suppose you love to cook and want to make some Indian food: Palak Paneer. You order the ingredients. The delivery picker returns your basket with all the paneer but the spinach is out of stock. Quelle horreur! Oh, the humanity! All your meal plans are now down the drain!

Instead, if you went shopping for Palak Paneer and did not find spinach, you could substitute it with Mustard greens to make Saag Paneer. This is why shopping in person becomes important. Only the customers know what they have in mind. There is a lot of complementarity in what people buy and substitutes are hard to figure out.

Rule 3: Being Dense. Grocery Delivery is “hyperlocal”.

Unlike apparel which is not perishable and can be shipped across geographies easily with scale, Grocery is special in that — the demand is “hyperlocal”. the number of people who look for groceries is far higher than people who searched for shopping malls (who cares?) or for haircuts (not that frequent).

So, the frequency of shopping makes the basket (order sizes) smaller. This immediately implies that the shipping fee/revenues for the shipping platform per order are very small. (Restaurant food delivery works sometimes due to better margins, but grocery margins are much thinner). Often, the delivery fee could be smaller than the wages often required to do the delivery. This is the reason why micro-fulfillment (Click online and pick up from the store) still remains a better alternative than delivery — it cuts costs by assigning part of the job to the customer.

Profitable grocery delivery would work for such small basket sizes would be if there was high demand density in a locality. (One main reason why grocery deliveries work so well in China). One can imagine the scale of delivery economies in Manhattan, downtown Philly or urban centers — but it is very hard to scale outside to suburbs and elsewhere.

So companies like Webvan and Peapod in the first Web wave, and now Instacart and Amazon Fresh have had great phases of growth — usually backed by buoyant access to easy liquidity — until they hit the fundamentals of the problem: Turns, Basket sizes, and Delivery costs. So, where are the efficiencies of scale in grocery deliveries? More as we go along.

Vishal Gaur, Marshall L. Fisher, Ananth Raman, (2005) An Econometric Analysis of Inventory Turnover Performance in Retail Services. Management Science 51(2):181-194.

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.1040.0298

https://www.driveresearch.com/market-research-company-blog/grocery-store-statistics-where-when-how-much-people-grocery-shop/#GSS13

Thank you for these insights and illustrating the complementarity problem with the paneer recipe. The hummingbird metaphor is also sticky. Wow, you show how one can make operations accessible and exciting for non-engineers.

I enjoyed reading this post (although I missed your usual cultural meanderings).

The palak paneer example resonated with me as we've had a few similar experiences. Nothing outrageous though, usually parsley for cilantro or one cereal brand for another. That said, it looks like others on the Internet haven't been so lucky. Some funny examples:

https://twitter.com/TrizzleMcDizzle/status/1246788213575950337

https://twitter.com/bexiparsons/status/1588229205883428864