The Sentinel #4: Writing, Love, and Toulouse-Lautrec in the Time of Chatbots

Generative AI will make our lives more meaningful

Will ChatGPT3 disrupt and change higher education? Will technology change old jobs or how people live? Yes, of course, in different and unexpected ways.

The discovery of synthetic dyes in Germany transformed the cotton supply chains, putting thousands of natural Indigo farmers in Bihar and Jharkhand in India into penury, burdened heavily by taxation and no livelihood. This eventually led to the 1917 Champaran Satyagraha, igniting perhaps the first non-violent protest against the British Raj.

Recently, ChatGPT3, the publicly available Large Language Model (LLM) owned by Open AI, has been making rounds in the higher education circles, as more colleagues explore the tool kit. There was an article about ChatGPT3 passing the USMLE — the entry test for practicing medicine in the US — although nuanced reports were mixed on how well it did.

The Financial Times declared that “AI chatbot’s MBA exam pass poses test for business schools” ($) — based on a white paper assessing its performance on a final exam, written by my Operations colleague.1 (I teach a follow-up course). My Wharton colleagues have been exploring how to integrate AI tools like ChatGPT into the syllabus.2

The performance of chatbots is stochastic as many have already observed. It also makes up facts along the way, and interestingly cites non-existent research papers in support of anodyne arguments. The performance may be lukewarm and unreliable, but I am under no illusion such models will do increasingly better at writing crisp essays and mathematical analyses in no time. Will it make me unnecessary, if AI can soon write a newsletter?

It is obvious that large language textual models have made leaps and bounds in improvement over the last decade. ChatGPT is only one of the many learning models being tested out at Deepmind, Google, and Meta. Then there’s Grammarly and Huggingface and such toolkits. Microsoft has invested heavily in Open AI.

We will soon see AI tools being employed in Microsoft office. There is already some evidence of the benefits. A recent MIT research paper shows that job applicants assisted with an Algorithmic Writing Service significantly improved their chances of getting hired.3

Some alarmist faculty on Twitter (not linking, sorry!) declared much of faculty jobs will be defunct soon. In contrast, I am firmly in the optimist camp.

I spent some time talking in the classroom about how to view them as tools. While immediate syllabus changes are interesting, in the short run I see two effects on education:

I see written exams and textual exams become less important, and “class time” together becomes more valuable.

Trust mechanisms in online education become weaker, increasing the value of in-person education.

But, how will lifelong learning look in an LLM-filled world? I argue that your identity and experience will become more important, in such an AI-filled world.

—

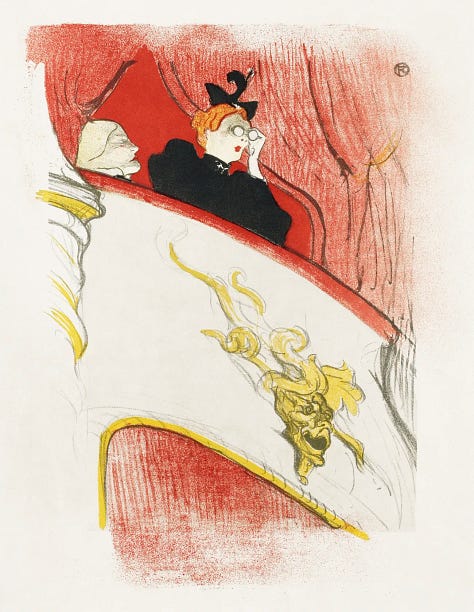

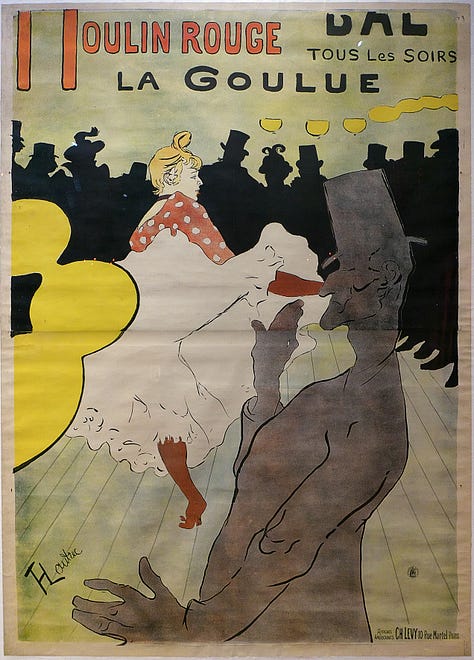

Art but also the Artist.

A favorite painting of mine hangs at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, a few blocks from my school. It is called A Montrouge (Rosa la Rouge) painted by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

My favorite moments at the Barnes Foundation were spent lost in the stunning picture that arrested my attention the first time and always since. The first time, I was sunk in the sound of the torrential downpour lashing on the glass facades with a monstrous resoluteness, matched only by the determination in her hidden face. Her red unkempt hair hides her eyes (Is she on the verge of tears? We don’t know). We see her grit as she stares into the distance. Was she a model (almost made up sounding name of Carmen), or a laundress at work, or was she a prostitute? Who surely knows? But it is clear, as the uncaring world flies by her, she is undeterred. She will see it all through. It brings the memories of many weatherworn faces.

Toulouse-Lautrec’s life was short-lived, dramatic, and tragic. He died at 36 from illness and syphilis. When he was a young child, he broke both his femur bones in separate minor accidents, and his legs stopped growing. He spent his adulthood in the small shell of a body that was probably considered a grotesque anomaly — a normally proportioned body with stubby short legs. Barely five foot tall, he walked every step in great pain, with a cane. If not for the accident of his birth in an aristocratic family, he would have been a full outcast.

He recognized the cruelty of his fate and the curious irony of his birth. He embraced it all by throwing himself headlong into the heady mix of emerging Parisian nightlife — cobblestones under dim gaslights, red powders of the dance girls, the noisy salons of Belle Epoque Paris. In reward for his prodigious talent, Toulouse-Lautrec was paid and patronized by the high society. Yet, within himself, it is clear, he was always on the outside. We can see his eyes watching the margins, those serving the high society — the dancers, clowns, servers, plongeurs, seamstresses, laundresses, prostitutes — then treating them in his art with the dignity that they deserve.

It is implied that Toulouse-Lautrec was crippled because of genetic effects from the consanguineous marriage between his parents; they were first cousins, who secretly married. The tenderness of their young love and the heartbreak of their union!

A ‘Close-Knit’ South India

It all strikes a chord because I grew up in South India — a strange place where such consanguineous marriages were common. In fact, Toulouse-Lautrec’s genetic disability reminded me of two friends, carrying the unfortunate genetic recessive traits displayed from cousin marriages. It is still shocking to me to recall how common it was in urban educated facilities that first cousins (children of opposite-gender siblings) married each other.

The Tamils, Telugus, and Kannadigas have among them a higher prevalence of cousin marriages. (In fact, there is a high fraction of cousin marriages among the Tamil-speaking majority in northern Sri Lanka — not in the picture). Kerala with its matrilineal practice is an exception. In North India, such marriages are strictly taboo among the Hindus. Almost all cousin marriages occur among Indian Muslims (explaining the slightly higher rates in Uttar Pradesh). The effect is probably more cultural than religious. There are more supportive data showing the gap difference between Pakistan and Bangladesh: between Urdu-speaking Muslims and Bengali Muslims.

In closed societies, marriages have always been economic arrangements between families. Endogamous marriages within castes continue to be the norm in India. As reported in the book, Whole Numbers and Half Truths,4 only 4 percent of married said their spouse belonged to a different caste group in a national survey. South India takes the norm one level stricter by keeping the bloodline within the family. I find in my conversations, this fact probably surprises a lot of Indians as well.

If you are not already weirded out, I’ll add a few more shades of color. Even though cousin marriages are illegal under the Indian Marriage Act since 1955, such marriages have been a constant trope in South Indian films. Particularly the ones set in the rural milieu, the leading lady earnestly waits in her hometown for her only love — I suppose that she must have only one cousin — to arrive back from the city after his graduation.

Essays and Wanderings

You did not probably expect to see a discussion of cousin marriages show up in an essay about AI. But, whenever I see Toulouse-Lautrec, I am reminded of this messy history. In a broken way, this essay is a human essay — quite imperfect and faulty.

Paul Graham once wrote that essay is like a river5 slowly winding to its natural conclusion. Perhaps human learning and writing is like the rivers, carrying impurities like typos, meandering in their oxbow bends, but serene with majestic calm. Yet, in Venice, there are beautiful canals, artificially created. At the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, I saw eager schoolchildren sketching the Nightwatch, a third of the painting created by Artificial Intelligence.6

In my mind, there is no doubt that AI will sooner or later write beautiful essays and create stellar pictures. Maybe, they will even create great memories. Philip K Dick speculated about these memories in his book “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” later made on screen as Bladerunner (1982). AI will generate many supposedly creative things that we do, such as writing and art. Where does that leave us?

Your Life is Your Product

While technology changes irreversibly alter our life (mostly for the better) and upend our jobs, it is good to remind ourselves what we do is a small part of what we are. I hope you did not reach here because you can use the good information. AI surely can provide one. ChatGpt can describe the painting nominally now, but I can see that personal preferences can be baked into its subjective opinions soon.

I hope you did not read this essay because I am a Wharton professor, which is only a small part of who I am. I hope that people read this essay because it is a view of my meanderings to figure things out. My observations on Mind and Craft.

Back to Art, Artists, and Dyes.

Toulouse-Lautrec embraced the newly emergent technology of color lithography allowing him to make fabulous brilliantly colored larger prints. Aided by technology during globalization, he paid homage to the Japanese vertical format, kakemono scrolls, and brought the style to the Parisian world.

We don’t remember Toulouse-Lautrec just for his lithography. He is a progenitor to Andy Warhol not merely because he embraced modernity. We remember him because of who he was, and how he saw something that was always there but never seen. He saw people like Rosa. And through their eyes, we see the worlds of yesterday and today.

Perhaps because of who he was, Toulouse-Lautrec saw the world differently from the tens of thousands of paintings that preceded him. He brought himself into art and thus, transformed art. Both the Art and the Artist matter.

We see the world with our unique lived experiences. Life is one sample path with million moments — just our own — distinct from the largeness of data fed into the tools we will use.

Generative AI, like lithography, will be a tool that will let us see new things.

Christian Terwiesch. https://mackinstitute.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Christian-Terwiesch-Chat-GTP-1.24.pdf

Daniel Rock.

Ethan Mollick. https://oneusefulthing.substack.com/p/the-mechanical-professor

Emma van Inwegen, Zanele Munyikwa, John J. Horton. Algorithmic Writing Assistance on Jobseekers’ Resumes Increases Hires. MIT Working Paper.

Rukmini Shrinivasan. Whole Numbers and Half Truths. https://www.amazon.com/Whole-Numbers-Half-Truths-Cannot/dp/9391234674

Paul Graham. http://www.paulgraham.com/essay.html

The Guardian. AI helps return Rembrandt’s The Night Watch to original size. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/jun/23/ai-helps-return-rembrandts-the-night-watch-to-original-size

Thank you for this wonderful essay (in true Montaigne fashion). I have to admit that I subscribed because you're a Wharton prof with operations expertise. But this is so much more. Keep it flowing.