The Sentinel #12: How did South Indian Movies get so good?

Two Old Cliches: Product-Market Fit and “Last Mile” Distribution.

With Naatu Naatu winning the Academy Award for the best song over heavyweights like Rihanna and Lady Gaga, I can write about a topic that I truly have expertise in: South Indian Films. It will be also the first India-related post of the newsletter.

Welcome new subscribers! This email now reaches 54 countries. Thank you for your support! South India seems like a niche topic to write on, regardless of my promise to keep this newsletter un-programmatic. Fear not, this post will still cover familiar terrain: culture, history, and the business of Operations. Nevertheless, I ask for your indulgence and patience.

I follow the same advice I give people visiting India: “Begin with something familiar”. At age 16, living in a world without mobile, landlines, and running water, I had seen more films than I had read books in English.1 So, I start with a topic I know better than any other: South India and its films.

A Definition

I find many Indians are poorly informed and/or dismissive about what they routinely address as Regional Cinema or sometimes simply, “South Movies”. Southern Cinema largely comprises films in 4 languages: Malayalam (understated inner life), Telugu (larger than life), Tamil & Kannada (somewhere in between). “South Cinema” is also distinct from the “Parallel Cinema” of Satyajit Ray and Adoor Gopalakrishnan.

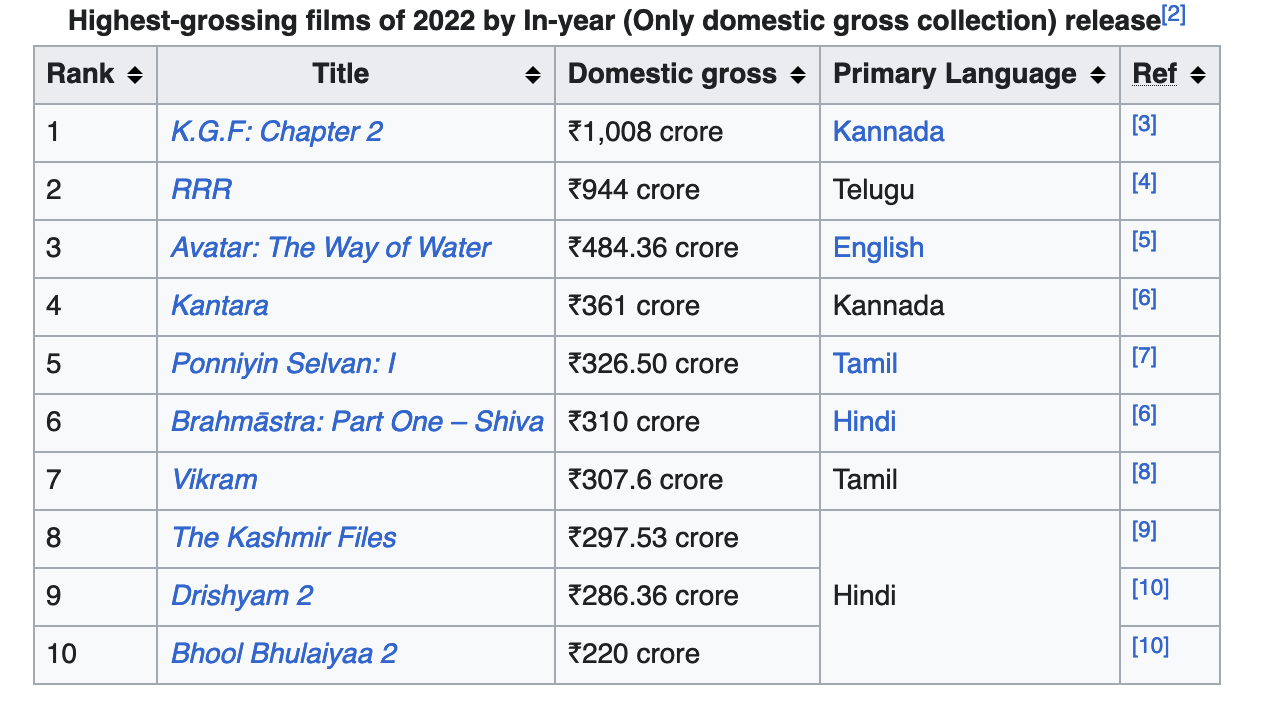

It has been of some surprise and some consternation, that the highest-grossing movies in India in 2022 were in regional languages. It is a remarkable fact given that 56%+ of the country speaks Hindi and the top film was in Kannada which is spoken by less than 5% of the population. It is equivalent to a small chain Whataburger selling more burgers than McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s, and Taco Bell.

So, how did they get that good? Instead of reviewing the films, I am going to look at the market forces that led to this point. The first reason is their market focus. To use the single most cliched expression in the valley, the …

Product-Market Fit.

To understand how the films fit the market, we have to begin the story in the 1990s with the most successful and perhaps most dangerous immigrant in the world 😊. Because he transforms things in unexpected ways everywhere he lands.

The Most Dangerous Immigrant

This person. Rupert Murdoch. Recall how much Fox News and Sky Network changed the US and the UK.

Indian broadcasting markets opened up when economic liberalization happened in 1991, under the aegis of PM PV Narasimha Rao, probably the most underrated Prime Minister India ever had. Rupert Murdoch made an aggressive bid to enter the Indian market and purchased STAR TV, a Pan-Asia network that existed in South East Asia. News Corporation purchased 63.6% shares of STAR TV for $525 million and escalated its commitment by purchasing all the remaining shares on the same day. Star TV became a wholly owned subsidiary of News Corporation, a Rupert Murdoch brainchild. Soon, new entrants would fill the vacuum of the market in the South, which was not reached by Doordarshan.

In the years before the 90s, the state-owned television Doordarshan (DD), literally “Distance Vision”, ruled the roost. Most of the programming was controlled by Delhi, with the marquee show being “Movie of the week” Hindi films on Sunday evenings. The planners at DD, allotted a couple of hours per day to “regional programming”, giving some time to more than 20 states and 15 official languages of India spoken by millions.

Most of the programming was watched as a community, with the entire neighborhood viewing at a house that had a television. My childhood TV memories were the clicks of the TV being turned off after those two hours. A large number of Indian households in the South grew up with no recollections of national obsessions like Hum Log or Buniyaad. When the National channel serialized two great epics — Ramayana and Mahabharata — it opened up the possibilities of what TV could be.

In the 80s Chennai, local newspapers would run translated transcripts of the dialogues for people to follow along, and then dubbed programming came along. This all sounds like the current TV landscape of continental Europe — a large number of American films on TV with subtitles (as in Norway & Sweden) or dubbed (as in Germany or Italy). But, there was an important difference. Indians are crazy about movies — so, in the world of humdrum TV, reaching less than 20% of the households — every year, there were 100+ films that were released in each Southern language.

Many Languages, Many States.

In the 1940s, India had hundreds of princely states (Green on the map above) which were integrated after Independence. Since the British expansion in India began in the South and the East, you can see vast stretches of red British India around Bengal and in the South (acquired through the Carnatic Wars). Almost the entire south was one unit as Madras Presidency under the British administration. It is from this history, the ever-endearing term Madrasi has stuck around (annoying the gentle Telugu- and Kannada-speaking folks, who want very little to do with Madras). After independence, this setup continued.

In 1952, Potti Sriramulu (another engineer who changed history!), went on a long fast, trying to persuade the first Indian PM Jawaharlal Nehru, then Prime Minister of barely 6 months, to cleave the Madras presidency and create a new state Andhra on linguistic basis, with Madras as its capital. (In the 1950s, Madras had a 20% Telugu-speaking population, which is currently at 10%). The JVP committee in charge of the planning refused.

Sriramulu continued his fasting and tragically passed away in December 1952. There were riots (perhaps the first in India with non-religious tones) in the aftermath of his death. The JVP committee eventually relented and created Telugu-speaking Andhra State in 1953 (the first linguistic state in India) with Kurnool as the capital. Linguistic Indian states were a natural certainty waiting to happen. It is fashionable nowadays to blame everything on Nehru. So, note that J and V in the JVP committee stood for J- Jawaharlal Nehru, and V- Vallabhbhai Patel (and P for Pattabi Sitarammiah).

Later, the princely state of Hyderabad was divided and a big chunk of it, Telangana, was added to Andhra Pradesh, and the city of Hyderabad was made the capital. (Now, they are divided back again).

Followed by a spate of protests and recalcitrant demands, several states were created following the Reorganization Act in 1956. Cochin, Malabar, South Canara, and Thiruvithamkoor (Travancore) were merged to form Kerala in 1956. The same year, the princely states of Mysore, Coorg, parts of Hyderabad, and parts of the British Raj in Deccan became the Mysore State (which eventually was christened Karnataka in 1973).

"Even before the states were linguistically reorganized, the default border of Karnataka was the last point where Rajkumar's films were being distributed," -Prof. KV Narayana, Linguist, Former Vice Chancellor of Kannada University.

Federalism & Economic Populism

The language of politics is often the language of persuasion and also the language of imagination. Hence, southern films are intricately tied to the political landscape and economy. While it is customary to poke fun at fan-struck South India for electing film stars as its leaders, films have always had the right pulse of society. Films acted as a cultural filter for political talent, weeding out those who fail to understand what people need. Films gave a medium for rebellious political expression against national oppression, and film stars became vehicles of those expressions.

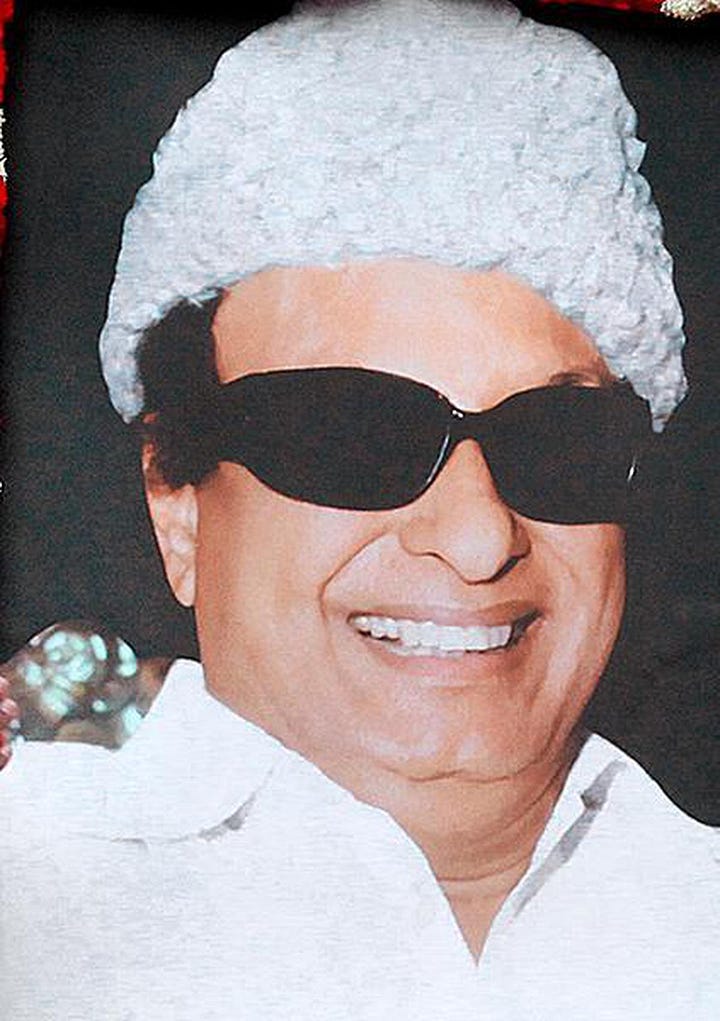

MG Ramachandran, a film star and immigrant from Sri Lanka, became the Chief minister of Tamil Nadu, after several leading roles in socially progressive films. Very Reaganesque in some ways, he was often dismissed as a showman, due to a lack of erudition or oratory skills. As an able administrator, MGR toned down language chauvinism and emphasized economic populism (that has come to be the hallmark of Indian National politics). MGR is now renowned for introducing the school midday-meal scheme by raising the sales tax (an impossibility now with nationalized GST tax). Much derided when introduced, this program eventually led to a substantial increase in girl child education and attendance — and eventually an increased female labor force participation in the state. (Of the 1.6 million women industrial workers across India, 43 percent were working in the factories of Tamil Nadu alone).2

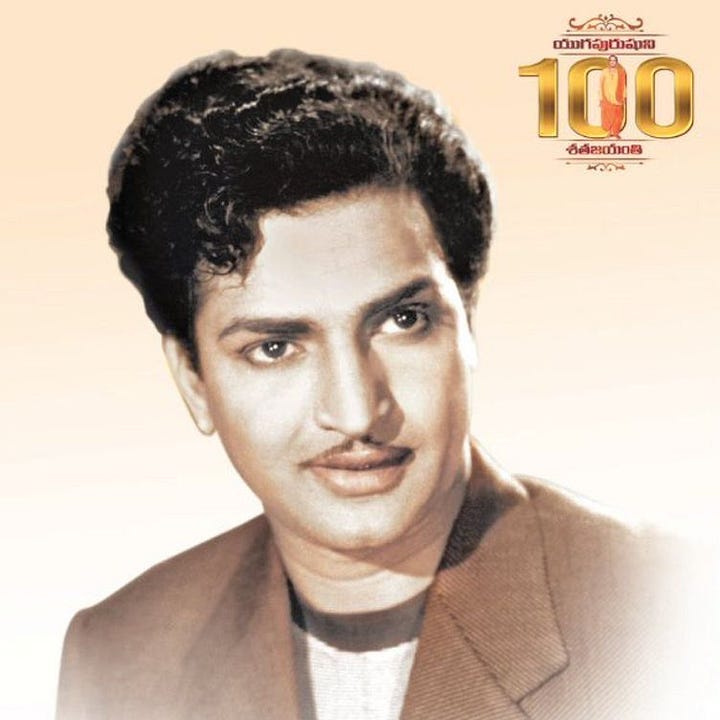

NT Rama Rao, a Telugu film actor, fed up with the continued Congress rule by diktat from Delhi (a perennial problem regardless of politics), founded the Telugu Desam Party (“Country of Telugus”) and within months won the election to become the first non-Congress chief minister of Andhra Pradesh. Many of his political innovations (cars retrofitted as chariots, populist speeches with film references, and a total embrace of Hinduism) have been ably adopted by future national politicians. By the way, the hirsute muscular actor in RRR, NTR Jr., is NT Ramarao’s grandson, now acting in far more progressive roles compared to his cringe-worthy early appearances.

Stars, Suns, and Talent Funnels

Rupert Murdoch’s Star TV entered this 30-year-old vacuum where films ruled the south. Almost, immediately, the first Indian private channel Zee TV was founded, and then SUN TV was founded by the Maran family. The name “Sun” is seemingly cooked up as unimaginative contrast with Star, but it has to do with the election symbol of a regional party (Rising Sun of DMK, a party connected to Murasoli Maran). In any case, it was such an un-Tamil name generated as a response to Rupert Murdoch’s Star TV. Soon, the market was flooded and eventually fragmented into a plethora of competitors, each with the backing of corporate and political families. Star TV went on acquire a few channels (Vijay TV for e.g.) but the competitive landscape made it harder for them to survive. Eventually, Disney (which was then struggling to break into India), acquired 20th Century Fox, which also included Star India.

As TV channels gained viewership, with many women staying home to watch soaps, South Indian films had to reinvent themselves by sharpening their focus and breaking genre conventions, but using TV as a talent funnel for singers, dancers, comedians, writers, and set-designers. Famously, among them is an impactful TV show “Tomorrow’s Director” which has identified great directors through a competition of directing short films.3

Last Mile Distribution: The Internet

So far, I haven’t quite explained why these movies have grown to be widely successful. It is often the laziness of incumbents and the cost of distribution.

First, Bollywood had lost its way. In the aughts, in the aftermath of the realization of a wider market, Bollywood films increasingly were catering to rich Indians living in the US and Europe. (A ‘running’ joke in our household is how in films, the stars go for a morning run all the way from Brooklyn through Battery park, to Central Park and back — a marathon every day). While Southern movies were laser-focused on their customers in their vernacular market, Bollywood was in search of the fickle patronage of emigrants and first-generation Americans whose interests had long diverged.

In some ways, South Indian movies are comparable to Korean movies: Under the radar, many years of being ignored, and over time, developing their own unique style of storytelling; an unapologetic dedication to the narrative regardless of its bizarre farfetchedness, emotive moments, and hyper-stylized violence. The movie RRR is a distillation of all of these qualities.

The pan-India reception was just one step away with the advent of the Internet and smartphones. The smartphone penetration in India exploded from 40m in 2010 to 700m in 2020. In 2017, I could see this sea change happening in small towns in India: On mobiles and on YouTube, demand was rising for South movies dubbed into Hindi (with atrocious titles like “Real Man Hero” or “Fighterman”). The working-class folks in the North were lapping up South movies — loud and lascivious but very local compared to distant Bollywood stories on rich families living in mansions on other continents.

The entry of Netflix, Amazon, and Disney Hotstar streaming solved another problem — distribution — by flattening the distribution costs and making international content appear on many TVs and phones, although Netflix seems to be struggling to crack the “language code” compared to Amazon Prime or Disney Hotstar.

Finally, what makes South Indian movies distinct from Bollywood? While they share many cultural similarities, I would identify five things: (a) heavy alignment with indigenous Carnatic and folk music, (b) surplus of technical talent: particularly editing and art direction, (c) classical liberalism: religious tolerance, education, women’s rights, and caste politics, (d) a blase embrace of everyday eroticism (but also jaded with racism and sexism), and (e) omnipresent political commentary.

Piqued? Where should you begin? That’s for a future essay if you are interested.

I did a quick calculating exercise with a close friend and we had now seen several movies in each of the 6 languages: Tamil, Telugu (200+), Hindi (100+), Kannada, Malayalam (50+), and Bengali (20+).

Dhruvika Dhamija, 2023. https://ceda.ashoka.edu.in/how-many-women-work-in-indias-factories/

https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/how-tamil-show-naalaiya-iyakkunar-has-changed-kollywoods-landscape-158338

Loved the history, I knew bits and pieces of it but it was great to hear a complete narrative. I feel like one more amplifying factor for RRR's popularity was stuff like Instagram and youtube short form videos. They break the traditional marketing geographical boundaries and get promotional content/ad campaigns to people who might like it (and onwards to national level virality)