Later, on a forlorn day on a local train platform bench in Mumbai, after a thoughtless blunder that put me in financial peril, with an opaque sheet of monsoon rains lashing sideways and drowning my tears, I would remember the warmest day walking to school, when my mother, in achingly hushed tones recalled a proverb for me.

It was second grade, and our homework was to bring a proverb. Sunlight glistened through the cotton-threaded veil of her sari, whose corner she held, as she always did, over my hair, perfectly oiled and parted with precision by an old ivory-green plastic comb with a million teeth, as I heard her finally respond to my persistent query to tell me a proverb that she knew. She sighed. Then, strains of a lifetime of memories in her voice came out: “Poruthar puvi alvar” (literally translated, those who are patient will rule the world, i.e., Patience is its reward), an Indian version of the biblical “the meek shall inherit the earth”.

I think of that day often.

So, on this somber Good Friday before Easter — this being a newsletter of contemplation — I wonder about the import and meaning of patience at the workplace. Meekness in the Bible is often associated with humility, patience, and forbearance, closer to the original proverb I was told, than the current conception of weakness.

Eventually, my financial predicament was resolved, only due to a patient individual who was willing to understand the complexity of the issue, hear out the nature of the mistake, and worked through a resolution. Just last week, I had an exactly opposite experience, of an individual who was impatient, and hastily insisted on moving on than resolving the problem. It is a learning moment — how good people and the right culture can change a workplace or an organization.

I mentioned Tech Downturn and high employee turnover in my essay on Operations Lessons from Sweden. It has been disappointing to see that some of the shine and optimism in the Tech industry has worn off a bit — as many firms impatiently hiring and laying off employees, as the apparel brick-and-mortar retailers had done over the years.

I started thinking about Zappos and how its founder Tony Hsieh emphasized: “Service can be a byproduct of Culture”. We should first start with the question:

Does Culture have anything to do with Product?

Perils of Numbers Trap

When I am not pondering ideas for newsletters or writing academic papers, I teach an Operations class at a university. The course covers, among other things, Supply Chain Operations which is often thought (and taught) to be a much a quantitative “nuts and bolts” course. However, I often warn students not to fall into the trap of data evaluation as soon as they see a problem.

It is dissonant advice, as I am usually an evangelist for analysis and analytics. Evermore than before, it is important to have a working model of things we see. Models explain many things, from the most mundane to the most intricate. For instance, we have envisioned models for how people walk around when they shop in a retail store. We have models for how people think about replacing their refrigerator in their kitchen or buying a house. Of course, for each person, the decision process is slightly different. A mental model captures the commonalities in these decisions while allowing for slight differences.

Models need not be quantitative, even though I love quantitative models. They help in being precise about what is included in the model and what is out of the model.

Mental Models as Recipes

It is best to think of models as a recipe for a dish — the ingredients can change, but the template remains usable even after those changes. Recipes don’t tell us much about the experience of tasting a dish, but just the process behind how a dish came to be. Models, like recipes, are great for reproducibility, but not always for discoveries.

Crucially, we should NEVER confuse the recipe for the dish.

Dishes are more than recipes. What’s food? Our food is transformed by disparate associations: the company we have at the dinner, the weather when we meet for dinner, the aching muscles after a long tiring day, and the Proustian memories that abound with smells and textures (like the food critic discovers in the movie, Ratatouille). Recipes have none of these features.

Far too many confuse business models for the businesses. A business can thrive even when the fundamentals “fail” to explain the business. How is that possible? Culture is one such fundamental “key” to business.

Products over Process

No one truly expected in the 1990s that Amazon would become the behemoth it has grown to be. Here is Jeff Bezos in an interview with Mathias Döpfner.

I remember, early on, we only had 125 employees, when Barnes & Noble, the big United States bookseller, opened their online website to compete against us, barnesandnoble.com. We’d had about a two-year window. We opened in 1995; they opened in 1997. And at that time, all the headlines — and the funniest were about how we were about to be destroyed by this much larger company. We had 125 employees and $60 million a year in annual sales — $60 million with an “M.” And Barnes & Noble at that time had 30,000 employees and about $3 billion in sales. So they were giant; we were tiny. And we had limited resources, and the headlines were very negative about Amazon. The one that was most memorable was just “Amazon. toast.”

Of course, one common operational question that is often asked about Amazon is why they started as booksellers. The fairly straightforward answer (with hindsight) is the Stock Keeping Units (SKU) variety in books.

We have the answer from Mr. Bezos himself. At the 1997 Special Libraries Conference, Jeff Bezos discusses why Amazon chose to sell books first. (Originally, from a Twitter post by Brian Roemmele).

I picked books as the first best product to sell online, making a list of like 20 different products that you might be able to sell. Books were great as the first best because books are incredibly unusual in one respect, that is that there are more items in the book category than there are items in any other category by far. Music is number two, there are about 200,000 active music CDs at any given time. But in the book space, there are over 3 million different books worldwide active in print at any given time across all languages, more than 1.5 million in English alone. So when you have that many items you can literally build a store online that couldn’t exist any other way.

Amazon always had the “Long Tail” idea pat down. If you ranked all the items that are sold in the books category, the highest-selling books (currently, a rags-to-riches memoir called Spare written by someone with the first name Prince, and last name Harry) sell multiple times more than low-ranked slow-moving books. Low-ranked items turn very slowly, and it is uneconomical even for a large bookstore to carry that, not just because of space limitations, but economic limitations.

Suppose a store has 30 copies of the best-selling book that sells out in a month. At this rate, they are roughly selling one book a day. Expressed in different terms, their inventory “turns” (nearly) 365 times in a year. (I talked about turns, using the same numbers, in Why is Grocery E-commerce So Hard?”).

On the slow-moving end, they could have a book that sells not over 1 or 2 copies a year (and hence “turns” one or two times). Books that are even lower ranked, turn even more slowly — not only slowly but also unpredictably. It is simply uneconomical to have one or two copies of hundreds of such slow-moving books in high real estate areas. Now, instead, put these slow-moving items in a warehouse in the middle of Idaho or Kentucky. It is easy to hold them for cheap as long as one can move them to customers quickly.

So, the more SKUs there are in a category, the smaller the fraction of the overall demand fulfilled by books in the store. As Bezos pointed out that there are 3 million different titles active in print and stores can only carry a few tens of thousands at best. The rest of the books are not available in any store, even though there is market demand for them.

By beginning in a category where most of the brick and mortar could not economically hold the inventory, Amazon was not competing with any company for selling those books, at least until the competing booksellers opened a website and warehouse. As the brick-and-mortar retailers (and a lot of competing web retail startups) were soon to learn, a warehouse and a website do not make an e-commerce firm. In the two-year span (1995-1997), Amazon had built operational capability in moving books (or any physical product) quickly to the customer.

Process over Product

To understand a company like Zappos, we must ask a different question: Amazon soon started spreading to other categories, but it took 10 years to shoes. Why did they take so long to sell shoes?

A pure-play e-commerce firm (like Amazon circa 2000) loses the consolidation benefits and gains a higher product variety. But, there is one more aspect that is important. Every time Amazon puts a new product line in the warehouse, it moves it away from a customer, further into the supply chain.

Every customer-obsessed innovation by Amazon has been in trying to get the product “closer” to the customer, on the web. Everyone has to open stores, eventually.

Books vs. Shoes

Despite the maxim to NOT judge a book by the cover, e-commerce gave us a confirmation that it was ok to buy books online, just by looking at the cover. What makes up an excellent book has very little to do with the “engineering” of the book. Of course, shiny pages, hardcover, handy size, beautiful font, and illustrations do describe a book, but they are not decisive features of the book.

Books are seen as erudite, and shoes, flaky. How wrong is that?

Shoes are things that keep us grounded. They bear our weight and tell every onlooker what kind of people we are and what we care about. Good shoes are friends that hug us through the day — bad shoes, those difficult relationships. The feel, the touch, the sense of buying it all matters. There is even a blog on pairing shoes with books.

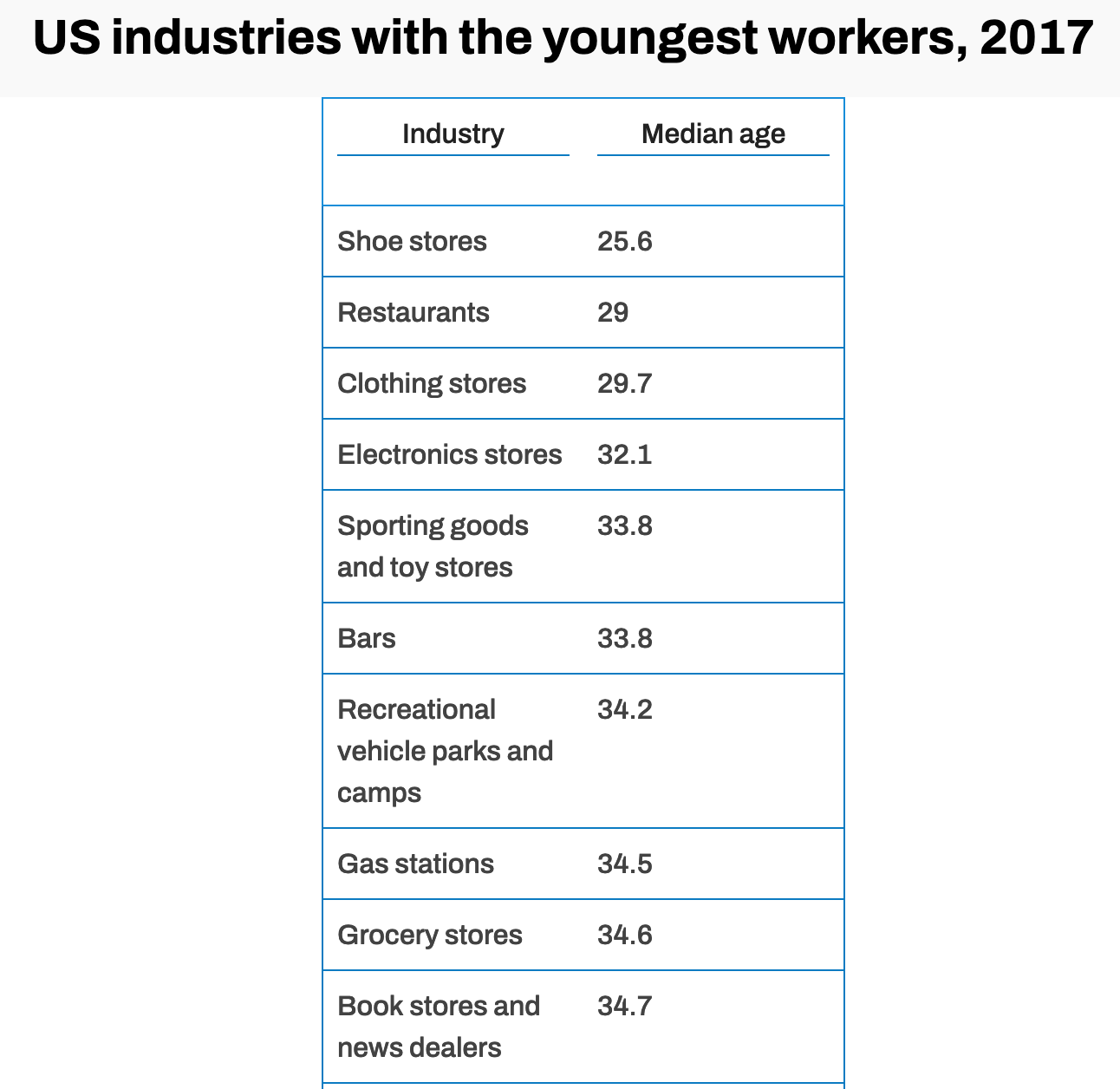

So, unlike books, to sell shoes you really have to understand the customer. But retail has been ignoring the value of experience in providing customer service — Shoe stores employ the youngest workers (median age 25.6) compared to bookstores (median age 34.7). This is the gap that Zappos filled.

The masterful accomplishment of Zappos was to move the product closer to the customer, by moving the “service” closer to the customer. This was only possible through culture. In many ways, Zappos was not a run-of-the-mill internet retailer. It was a strikingly original idea, both in audacity and execution. For instance, customer service was not based on throughput (the usual goal in the efficiency age), but on making personal emotional connections and solving customer issues. For example, 1

They answered the phone cheerfully but without a script, a standard tool for most phone reps. They were not compensated on how many calls they handled during their shifts but were told to spend as much time with customers as it took to resolve their issues. Zappos even kept a record of the longest customer call—the last was on July 10, 2010 when a CLT member spoke for 7 hours and 28 minutes.

As the founder, Tony Hsieh himself stated succinctly:

For individuals, character is destiny. For organizations, culture is destiny.

It has been two years and more since founder Tony Hsieh left us, and post-pandemic tech is beset with challenges. But this is the time to be “Delivering Happiness”, by betting on people. By, trusting people to solve problems and ideate new solutions to constraints.

Chag Sameach! Happy Easter! See you next week!

Source: Zappos: Happiness in a Box. Aaker and Leslie. Stanford Case Study. 2010.