Since the time I wrote the post “Apple as a Service”, a couple of weeks back, through reader emails, I discovered two separate developments. (I love emails. Just hit reply on the post in your inbox).

First, this article in the Wall Street Journal ($, unfortunately) by Christopher Mims on how Apple iPhones are now sticking around longer, with long use-life. Essentially, the obsolescence costs for Apple iPhones are decreasing, allowing Apple to expand into supporting old devices and services! A point I made in the newsletter couple of weeks back (although with a different goal, trying to explain their Buy Now, Pay Later plans).

Particularly, Mims wrote,

… when I wanted to give my youngest a device to occasionally play games on, I handed him my old iPhone 8—which is still generating revenue for Apple, through a $5-a-month Apple Arcade subscription.

It seems an acknowledgment of how Apple is using its long-shelf life products in service revenue streams. Here is the key quote:

From hardware to services revenue

You might think that the sale of used devices represents a threat to Apple’s overall revenue, by cannibalizing new phone sales. But Apple has found a way to make money on nearly all iPhones, even when it doesn’t get a cut from the sale of a used device.

Last quarter, Apple generated a company record $20.8 billion in services revenue, due in part to 935 million paid subscriptions to Apple’s own services. Those services include apps, iCloud and Apple Music. That represented almost 17% of the company’s revenue for the period. Because the margins on services are much higher than on hardware, services represent an even greater share of Apple’s total profits.

In my post, I also speculated if and whether Apple was a bank.

Particularly, more movement came in that direction, with Apple launching their high-yield savings account that pays an annual percentage yield of 4.15%. As mentioned, Apple partnered with Goldman Sachs to offer consumers those options, as it continues to change its phone from a “call people machine” to “it is a digital wallet” — essentially connecting to its payment services.

The savings accounts require no minimum deposit and the maximum balance of $250,000. (Although with what happened with Silicon Valley Bank, it is not unlikely to expect that customers are protected even with higher deposits).

A funny data point. Apple’s offered interest is higher than the interest rate offered under Goldman Sachs's own card, Marcus. (At a later date, I will write about my experience accidentally working for Marcus advertising). But remember this is not a bad deal for Goldman Sachs (GS) in that GS gets to service all the loyal Apple customers. This is a tiny cost to get a list of loyal customers. Frankly, better than an acquisition like Frank.

So, I am happy to be right, given how wrong I have been on many things. On to new issues.

Being Number One

Over several posts, I have covered the triptych of my responsibilities: duty, dad, and desi, a half-endearing term for originating from India (desi means ‘from the nation’).

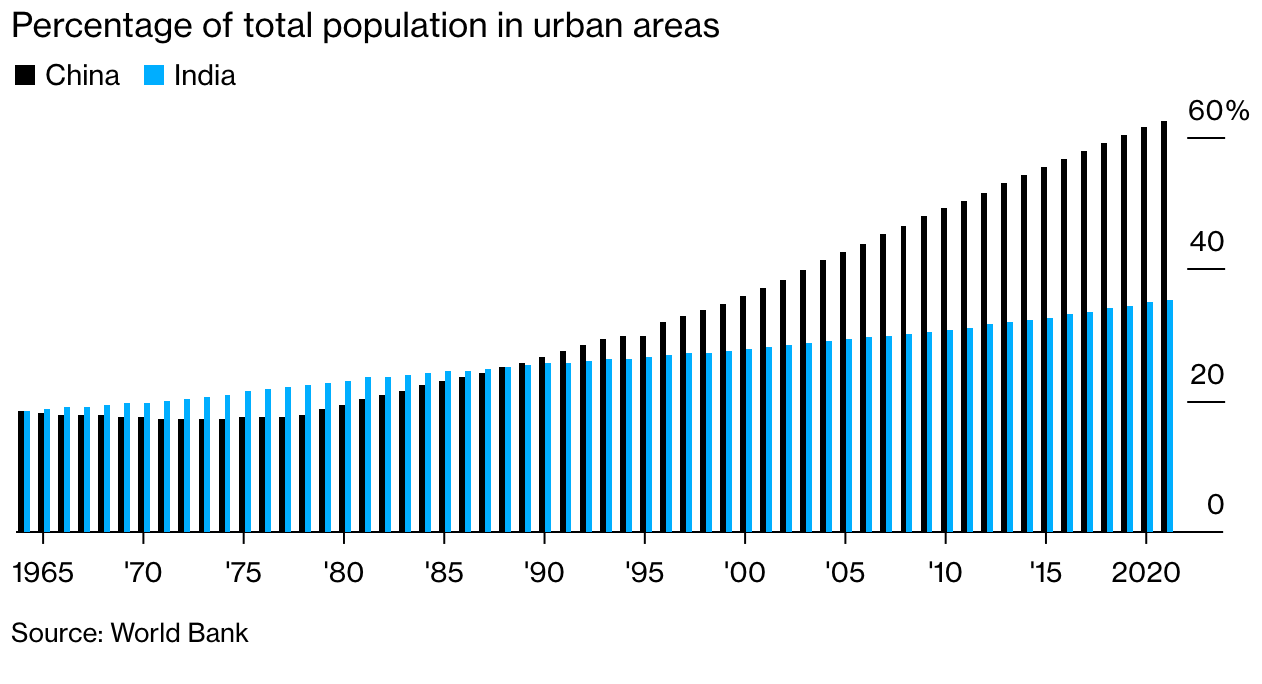

Recently, India crossed China as the most populous country in the world. When did this happen? I like inventories and I like people. I have loved saying that in Operations we treat people as inventories. Like inventory, it is too costly to count people every day. So questions about precisely when something happened rely on guesstimates.

Anyway, it’s all great news that we have so many people in a country. I love crowded places because you can be yourself in crowds. Your solitude is your mind and your experience is the world.

Look at the population board and imagine how much of the discussion in the developed nations (including this blog) is often over things that are immaterial to the concerns of the world.

India and China have had a long, cold relationship. The adage that good fences make good neighbors is very true. The recent history has both India and China warily staring across the borders mostly drawn out of thin air by the British (who else?) while being mutually respectful of their neighbor’s ancient histories. Hence, weird and highly controlled skirmishes (comparable to mixed-martial-arts cage matches) have transpired on the porous borders.

Back to population data. Mainly due to the highly controversial and ill-advised one-child policy, China’s population has slowed sufficiently enough that the workforce is diminishing by one Germany every few years.

Not only does India has the most people as a country, but it also has one of the youngest populations, with a median age of 28. That compares with about 38 in both the US and China. This age advantage could play a critical role in unlocking economic growth. India’s population continues to grow at a rate faster than the world average. So, I think the population is going to be at numero uno for a while. (Also No. 1 in the number of films made, another minor obsession of this newsletter).

Nevertheless, some challenges remain, but it helps to understand India from two different lenses: (1) India as a Market and (2) India as a Manufacturer.

1. India as a Market

One of the exciting things about India is how it has grown as a market. A commonly provided complaint is India is largely rural, which is definitely true, but this observation misses the whole point of what makes India appealing as a market. It is not the revenues, but the volumes, the young population, and its aspirations.

About 11% of India is now learning in English, but if you look at the top 20% of the income group (table below), 77% of the education is in English. Learning English is the biggest difference maker in careers (as it has been for me). English education at the elite end in India has had an enormous positive externality for the whole world — the CEOs of many Fortune 500 companies have been Indians. (Why? That needs another post in the future — but something to deal with growing up in large numbers and thinking in the midst of a cacophony of opinions).

For a company like Apple, which makes products at sky-high prices and margins, the expenditures of the English educated population are helpful. Apple is competing for the mind share of the top 20% of the population that owns phones (nearing 900 million now). In a country where the Android operating system has made deep inroads through widespread and cheaper mobile models (Oppo, Xiaomi, and Vivo are from China, and Samsung is from Korea) two things are helpful for Apple: (a) the prevalence of English-speaking culture and (b) the aspirations of the upwardly mobile (no pun intended).

Apple is a very aspirational brand — the high price only reinforces the image. While Android phones have been ahead in terms of features (AI, camera hardware), the nouveau-riche of India desires a brand like Apple. Apple was only 1% of the market share in 2017, and now at a small 4% in terms of volume but in terms of the value of revenues, Apple captures 18% of the market revenues.

So, when Apple opened its first store in India last week, it chose the Bandra-Kurla Complex (BKC), a suburb of Bombay. The joke is BKC is full of residents who in their minds live in America. An up-and-coming neighborhood in the 90s, BKC has now replaced South Bombay as the “hot spot”. Tim Cook was in India opening an Apple Store — which I called the biggest innovation by Apple — in BKC, among throngs of celebrity crowds.

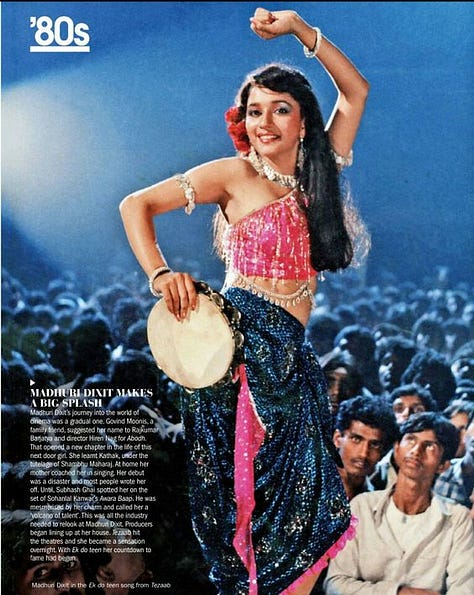

Then there was Cook, visiting hospitals and malls, meeting PM Modi, attending an IPL cricket match, and hanging out with Bollywood royalty (the last two are one and the same thing). Then again, there he was eating Vada Pav — an Indian burger of sorts and my favorite street food — with starlet Madhuri Dixit.

In writing this essay, I learned that Vada Pav — a deliciously simple vegetarian street food, fried potato vada sandwiched between fluffy bread slices — itself is a recent invention. Vada Pav comes from vada meaning fritters, and pav meaning bread from Portuguese “pao”. BBC reports that the dish was invented in 1966 by a Mumbaikar, Ashok Vaidya, who opened the first Vada Pav stall opposite the Dadar train station. Dadar — a few stations on the suburban rail line from my alma mater IIT Bombay — was the main station through which thousands of mill workers traveled on their way to work in Bombay locales like Parel and Worli. Vada Pav offered a simple non-messy, inexpensive transportable snack. Later, a distinct cultural figure Balsaheb Thackeray, the founder of the Shiv Sena political party, exhorted Marathi people to make Vada Pav their symbolic icon, (probably resisting the over-present South Indian and Gujarati influence in food in Bombay). Even as the steel mills collapsed in Bombay, the humble Vada Pav persisted and has come to be the iconic food of Bombay's blue-collar street food experience.

In my opinion, in the tech-affluent Bay Area, the best vada pav can be found at Puranpoli, a nondescript Marathi food joint a few blocks from the offices in Santa Clara.

In Apple as a Service, I argued that Apple is making inroads into the customer population with a lower willingness to pay by offering loans and credits. Another way to make that progress is by making lower-value products that sell for lower revenues. In India, where the prices historically have been low, the older, mature products help to make inroads into the market.

With India growing as a market for the foreseeable future, I can see the top income segment in India subscribing to Apple TV+, Apple Fitness, and such products. While those customers can be a part of Apple’s service portfolio, it is also important for Apple to broaden its base through manufacturing. The Indian population has had a history of admiring ‘homemade’ products: this shows up in waves of economic protectionism and economic populism, two sides of the same nationalistic coin.

2. India as a Manufacturer.

Unlike India as a Market, India as a Manufacturer faces specific challenges.

While researching for this post, I looked up “Apple plants in India” and went into a rabbit hole about grafting honey crisp apples in India. This is very much a reflection of the rural nature of products in India, and Apple’s current market penetration.

Manufacturing older, mature products such as iPhone 12 helps with market penetration but are also easier products to work on shift manufacturing. The experience of having made thousands of these products in China can be used to tackle quality control and problem-solving.

Apple is shifting capacities due to the secular trend of wage increases in China. But, partly Apple does not want the downstream manufacturing (which requires an uninterrupted supply of TSMC chips) to be swayed by geopolitical tensions between US and China.

Infrastructure is currently a challenge, but it can be overcome for specific manufacturing plants with effort. The country also is facing acute water problems, especially in the South where the Apple plants are located.

Currently, the bigger problem is labor supply. India needs educated engineers and a skilled manufacturing labor force. It is ironic I say this, given the population growth. Close to a third of the nation’s youth are not in any kind of employment or training. Only a small proportion (5%) of the country’s workforce is recognized as formally skilled, and the schools and universities that insist on written exams and tests, face the daunting task of directing labor toward practical engineering.

One of the important challenges that I have already spoken about is the low female labor force participation — an issue I discussed in the post on “Lessons from Sweden” — which is a pernicious problem in India.

Currently, Apple assembly in India is being done by Taiwanese companies: Foxconn and Pegatron in Tamil Nadu, and Wistron, another Taiwanese rival company, in Karnataka. Currently, they make up only about 5% of Apple’s overall global production, and Apple would like to increase that to 25%. But, the scaling hasn’t been easy.

In the Tata-owned factory in Hosur, Tamil Nadu that supplies to Apple, the yield is only 50%. One in two components (casings for iPhones) fails the quality test, which is far behind the productivity in the Zhengzhou factory in China. My colleague Ken Moon has a wonderful paper on how much learning is accrued from experience in manufacturing lines with a less turnover-prone workforce, which can save 4-5% on production costs based on a productivity study in an iPhone plant. The paper is just out in Management Science ($, link)1

There has been news about Wistron quitting India due to labor unrest and poor conditions in Karnataka. Karnataka is a state that is ruled by the same party that is in power at the National Center - BJP. So the problems are not political differences between the state and the center, but some structural difficulties in adjusting investments.

This is not to say the conditions are hopeless; I am certainly quite hopeful that these hiccups will be resolved. The problem of kickstarting manufacturing needs consistent effort and a much harder task than opening an Apple store in Bombay and Delhi.

One terrible suggestion that I have heard was that Apple should get proficient with “Jugaad” — making do — an expression that Indians use, to indicate resilience, but mostly comes across as skirting the rules. There is definitely something praiseworthy about overcoming constraints, but “jugaad” has often been used to justify poor governance, incumbency advantage, and license raj. India needs to let its states experiment and compete as the provinces did in Deng-era China: proficient in manufacturing, moving up the value chain, and steady industrial policy.

The crux of this essay: Apple is making two bets in India. One, India as a market, is an easier bet for Apple. The second one, India as a Manufacturer, is a more complex bet for Apple, but, also a more consequential bet for India. I am hopeful both bets work out, but the second bet will lift more people out of poverty.

Ken Moon, Patrick Bergemann, Daniel Brown, Andrew Chen, James Chu, Ellen A. Eisen, Gregory M. Fischer, Prashant Loyalka, Sungmin Rho, Joshua Cohen (2022) Manufacturing Productivity with Worker Turnover. Management Science 69(4):1995-2015.

I worked in a factory in 2006-2007 which was a vendor to Nokia which was making 50m + phones annually from its Sriperumbudur factory. Nokia's supplier development effort was the exact opposite of "jugaad" and closer to a tough sports coaching program - thousands of quality audits and 5-why reports later, they pretty much coached us into a textbook lean operation. I'm still in awe of how good their operational processes were. Our yield was pretty atrocious at the start, but we were competing favorably with their established chinese supplier towards the end. My experience tells me that Apple has a path to success but it requires a lot of patience, consistency and continuous improvement.