The Sentinel #8: Books as a Sustaining Technology

Roald Dahl, Childhood and Learning about Society.

Welcome new readers!

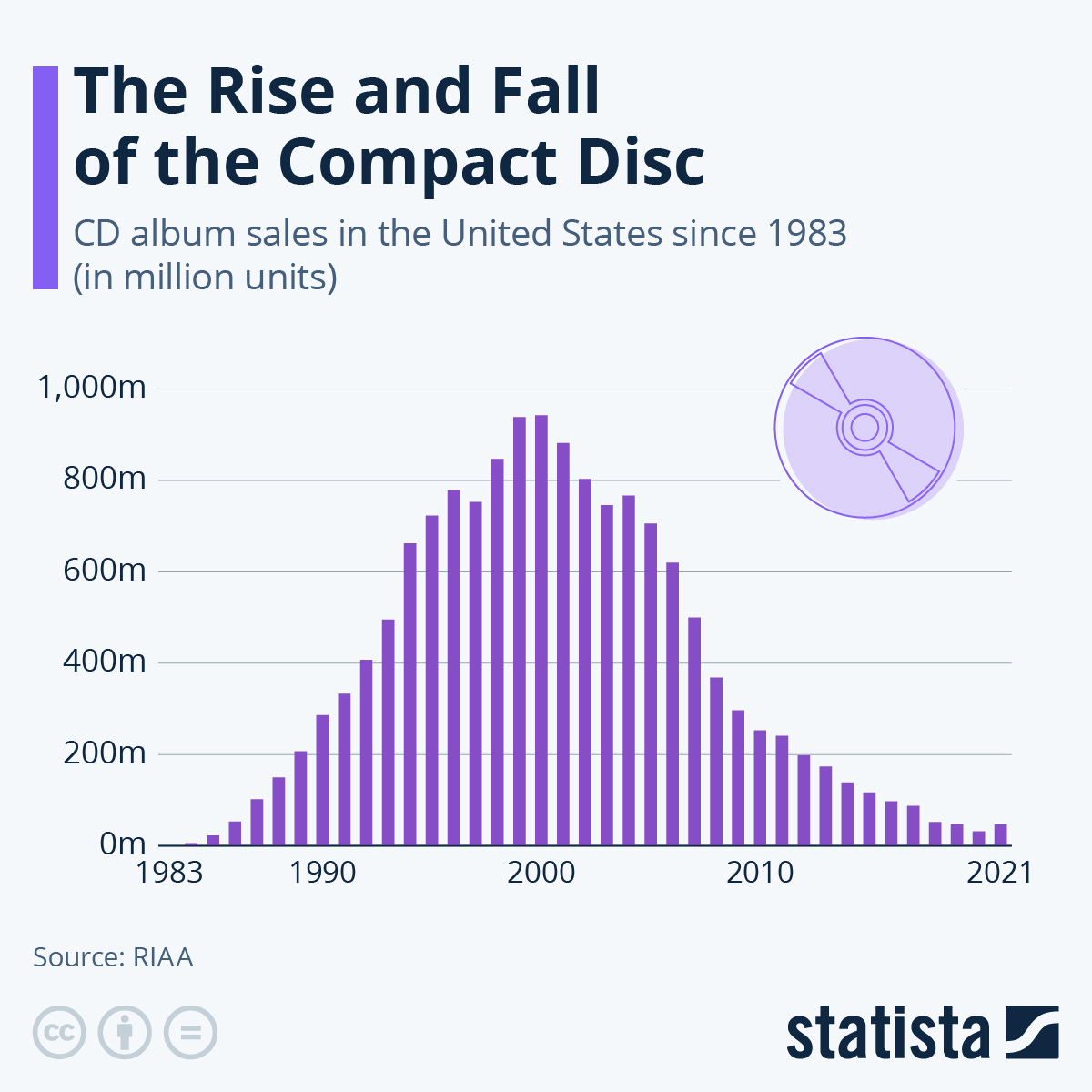

In this newsletter, I like looking at the role of physical goods in an increasingly digital world, as we did in the role of stores in grocery e-commerce. However, we all know that video stores and music stores are now nearly dead.

If you look at the evolution of music consumption through technologies, we can immediately see the birth and death of various technologies (vinyl, tapes, CDs). Last week, I pulled out an old CD to play a favorite, “God Give me Strength”, a collaboration between musicians Elvis Costello and Burt Bacharach (RIP!), but had no device to play it. I finally listened to it on YouTube. Increasingly, streaming is our way of consuming music, films, and other aspects of culture.

Books.

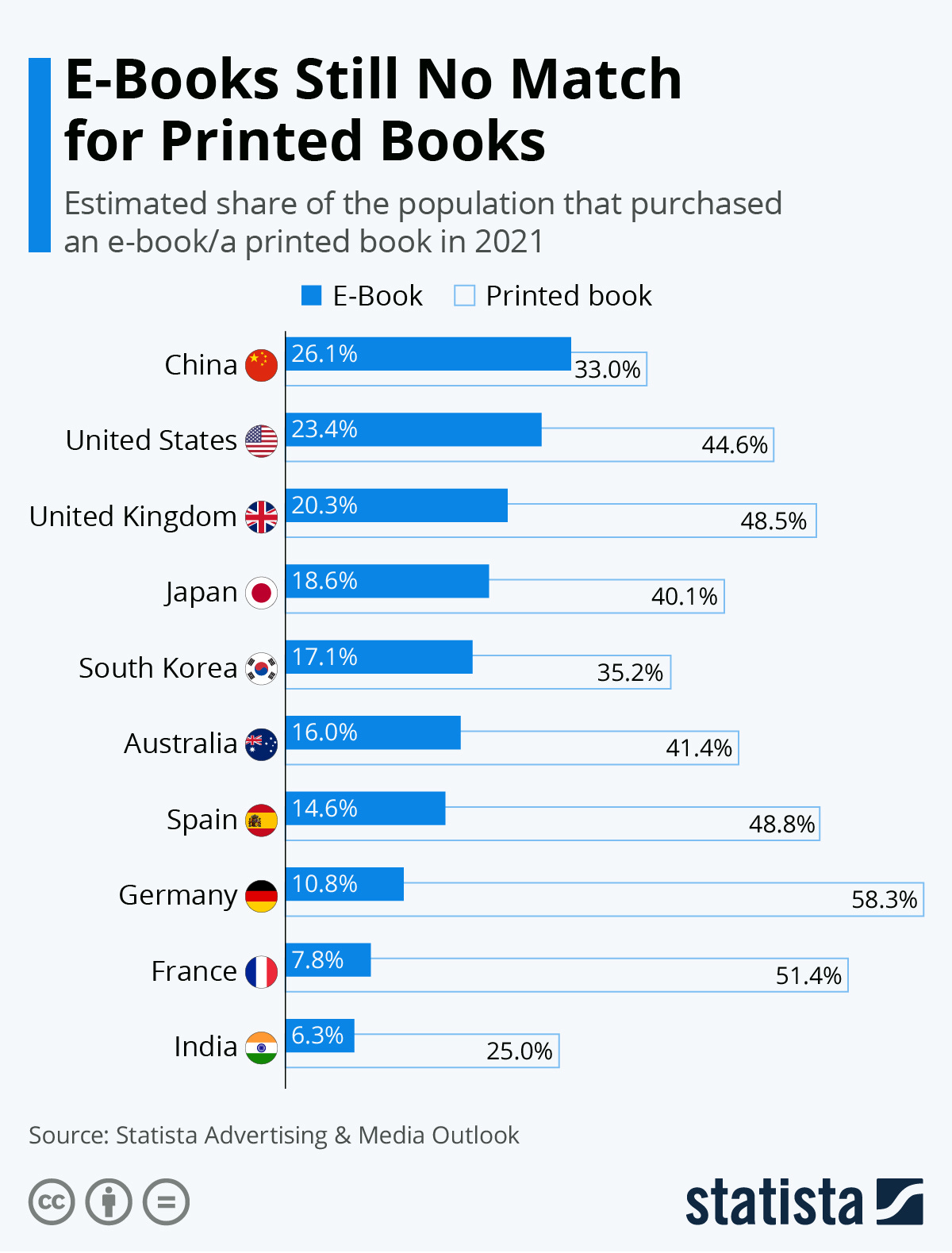

Despite all that explosive growth, books have remained a steady technology that has been hard to replicate or innovate. There is no “Han shot first” culture meme associated with books. They have been banned, burned, banished, and have continued to survive. It has been hard to disrupt books.

What makes physical books work well in the modern world? Don’t get me wrong. I read e-books. They are convenient, portable, and efficient. But, when I try to remember a time when I read something, I am always reaching out for the notes I made on my dog-eared copies. Books are a treasure because they are an archive of our growth.

Roahl Dahl and Naughtiness.

Let me begin with the recent kerfuffle over Roald Dahl, the English author of Norwegian origin, famous for his books for children. My young kids love his books. They are a big favorite in our house: Fantastic Mr. Fox and The Witches are their best individual picks. So, this is a topic close to home.

The publisher edited the "offensive language" out of his books, with the permission of his estate, Netflix, and others who own the copyright for his books, under the advice of a consultant (Inclusive Minds). So, I suppose it’s all legal and within the ambits of copyright law. The usual social operatives were at it again: the smattering of obsessives blaming it on people getting too sensitive. Luckily, Salman Rushdie1 and PEN America stepped in to describe what the effort is — a clear case of bowdlerization.

It was all bemusing to me, because I came very late to Roald Dahl, having started to read in English in my late teens. The first Roald Dahl I read was when I was 17 during my undergrad!: “Kiss Kiss” — a story collection for adults2 that predates all of his children’s books that have occupied the popular imagination. Before long, I read “Switch Bitch”, another collection of very adult short stories filled with macabre, twisted, but delicious, irreverence. Soon enough, I read many of his tales for children. In a way, I approached his books almost chronologically — I was always amazed at how much subversive takes he preserves in his books for children.

So, given the history of how he came to write children’s books, I am more bemused. What are we trying to protect for the children?

I suppose that many (like my own kids) are introduced to Roald Dahl at a young age as a children’s author, and are shocked that his values (both personal and on print) are transgressive. Roald Dahl is no saint — with recorded antisemitic views, and his books are peppered with not-unusual racism and sexism. He was a “work- in-process” 3 like all of us, renouncing some retrograde views, and modifying his work to refute outright racism (read up on the original Oompa Loompas). Yet, the distinguishing feature of his work was his absolute mastery of cheeky violations — constantly pushing the envelope. The effort to sanitize his words misses the whole point of pervasive irreverence in his work.

BFG, he titled the book. It is the Big FRIENDLY Giant, you see?! Not BIG F— Giant. (Come on. Empty the dirty thought from your head). I love the squeals of my kids, (who are vegetarians, no less), when they read about giants eating “human beans” — and in how they delight in names like Fleshlumpeater and Bloodbottler. We are all disappearing into our magical internal world of gruesome fairy tales.

The best strength of Roald Dahl’s books is that they find humor for children in sad, broken places. Moreover, it engages with the world head-on rather than avoiding it. All over the world, a number of kids are born into and raised in abject poverty. Their childhood dreams are broken by everyday real-life disappointments. Yet, there is joy in their childhood - fledgling, poignant, and ephemeral.

Mathilda has no logical reasons to be happy. Her parents are terrible humans; her teacher is positively evil — force-feeding kids, hurling them by their pigtails, and sending them to “Choker” — a sort of “Iron Maiden” built for the kids. Torture, bullying, and inhumanity thrive. Even a day in these conditions would be a nightmare. Yet, Mathilda is stuck in this world for all her young life. She is a cheerful kid living in a world of sadness, rescued by being lost in books, and the magical world of intellectual solitude. Yet, on the outside, a war of survival rages. (The musical is a failure because it tries to sing its way out of the horror; in the books, the reality is literal and magical).

In Roald Dahl’s stories, adults are barely saintly as they are in the real world. Parents are often terrible. If they are honest and good, they are snatched away in a gruesome miserable accident. Invariably, the kids are orphaned, bullied, and thrown out of home & live in abject penury — and yet, wake up, smile and form friendships and look forward to the next day. It allows them the joyous space both in reality and imagination, to vanquish the temerity of evildoers, and modify the laws of nature. This is why, the best works of bildungsroman, such as My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante, tackle head-on the distress of diverging futures kids face — even friends from the same tough neighborhood.

We bring kids into this world, through our veins held captive to moments of passion, programmed by years of propagation. Yet, as anthropologists say, over thousands of years, in our evolutionary drive to wander and forage, human gestation periods have decreased. So, unlike calves and cubs, who are up and running within hours of being born, our infants are helpless even to crawl or even turn over. This is nature’s ultimate joke on our young ones — the threat to life is not from another species but from the society we set up.

In Dahl’s book, The Witches, the protagonist kid has no name. (What a great choice! It could be any and every kid). The ending shocks adult sensitivities as the nameless kid remains a mouse. The witches are vanquished, but the damage is done, we adults think. Yet, kids don’t find the ending shocking at all. It is so clear as the day, to every kid, the world is wild and unsafe for him. Grandma’s hug is safe even if you are a mouse.

Every day, in America, we hug our kids and kiss them goodbye to schools and colleges dotted with stories of Sandy Hook and Uvalde. Nine grand wizards in black robes believe this is what freedom means. To adults, everything is a tradeoff.

We know that the world we built is much too cruel for the kids. Indeed, we hate for them to grow up fast, and yet pretend it’s only the words that hurt. All cruel adjectives and rude epithets in Roald Dahl’s work — fat, dark, brown, ugly, wicked, crooked, and many more — enrage and bother the adults. Once that meanness is sanitized, maybe we can all go back to pretending that the world is safe for children.

Books, Technology, and Information Corruption

The helpless blindness and learned pretense pervade the technology of editing. We mess around with information, when it is easy to edit things, and then obscure things as if they did not exist before. It defeats the true purpose of learning, the difficult evolution from mistaken beliefs to understanding, by living through it.

Our big failure as a modern society that builds newer technologies is the misguided focus on words over their meaning. We clamor for an edit button on Twitter, because it is important that our ephemeral thoughts (that no one remembers) be typographically correct. How much thought we put into words we say, than what we say!

Words are easy & effort is hard. ChatGPT creates lines of (really bad) poems with no soul, picking them from “bags of words”. As the Vanderbilt University fiasco demonstrates, we have no more words to console students every time tragedy strikes. So, instead of taking actions that put normalcy in jeopardy, we AI to generate “the right words”.

This is why physical books are sustaining technology. They are an archive of the world as it was. One can’t withdraw all the books back to edit them. When I read an old book, I learn how the world has evolved from then.

Physical books are really photograph albums of us at various points of our lives, snapped when we were their reader. We may not remember all the details in a book. When we open a book, we see mental snapshots of us reading the book and learning how far we have come since that moment of pure bliss.

Until next time, I leave you with…

PS: “God Give Me Strength” from Painted from Memory.

"Roald Dahl was no angel but this is absurd censorship. Puffin Books and the Dahl estate should be ashamed," Rushdie tweeted.

The Pig is a story that still makes me shiver. Dahl pokes fun at not being prepared for the world.

We are never very far away in this newsletter.