The Sentinel #31: Tariffs, Part II: Constraints on Manufacturing Locally

Five Challenges Facing "Make in America". Storms, Seas and Stability.

Preamble:

The word of the week is Tariff. While researching for this post, I found that English “tariff’ (taxes), the French “tarif” (rates) and Hindi/Urdu word “taarif” (praise) are variations of the same Arabic word meaning appraisal.1

In Part I of the essay, I wrote about economic costs caused by tariffs from a historical perspective. Instead of trying to argue the politics of tariff (there are many articles on the web talking about such on the internet), in this second part, I focus on manufacturing in America.

Trembling Hands, Steady Hands.

It is a funny world in a tragic way. We are living in a path of the trembling hand. Strange things occur on those paths!

The 1994 Nobel laureate, economist Reinhard Selten propounded the concept of Trembling Hand (Perfect) Equilibrium — an equilibrium that is sustained even under irrational strategies caused by trembling hand errors. It has never been more salient to design a market and incentivize reaching a good equilibrium that is impervious to such deviations. We need a composure that is not broken by the absurd strategies and impermanent waves.

I was thinking of Seneca the Younger’s statement: Stormy seas, Steady hands. As the state of the world keeps changing with every new smidgen of information, it is important to compose a stabler view. That is the goal of this post.

Here are 5 challenges facing Manufacturing in America. None of them are solved by high tariffs. I am a hopeful person, and I would love to see manufacturing flourish. It will only do so when we take patient, powerful steps to address the issues.

1. Skilled Labor Shortage.

It is tempting to think large scale manufacturing outsourcing is about low costs. Of course, costs do matter, but this is a common first order fallacy to base everything on costs. Companies now go to manufacturing locations due to the availability of skilled labor. Don’t hear it from me — hear it from Apple CEO Tim Cook.

As an example, Apple now makes phones in India.2 Despite cheap labor, manufacturing growth has been lukewarm in India, mainly due to relative lack of labor skill and managerial talent. In fact, most manufacturing within India takes place in locations with high labor costs (i.e., in the South).

The biggest impediment America faces is not labor cost per se (although cost is high). It is the shortage of skilled labor for most supply chains. For historical reasons, auto manufacturing has persisted (but with significant challenges in all directions, design, decisions, unions). But, there is no large scale labor available outside of that. Here are two examples:

Foxconn couldn’t find enough workers in Wisconsin,

and

TSMC doesn’t find enough engineers for Arizona plant.

This problem exists is mainly because improving productivity and scale requires significant amount of employee training and unwavering employer commitment.

2. Financing Manufacturing and Hardware.

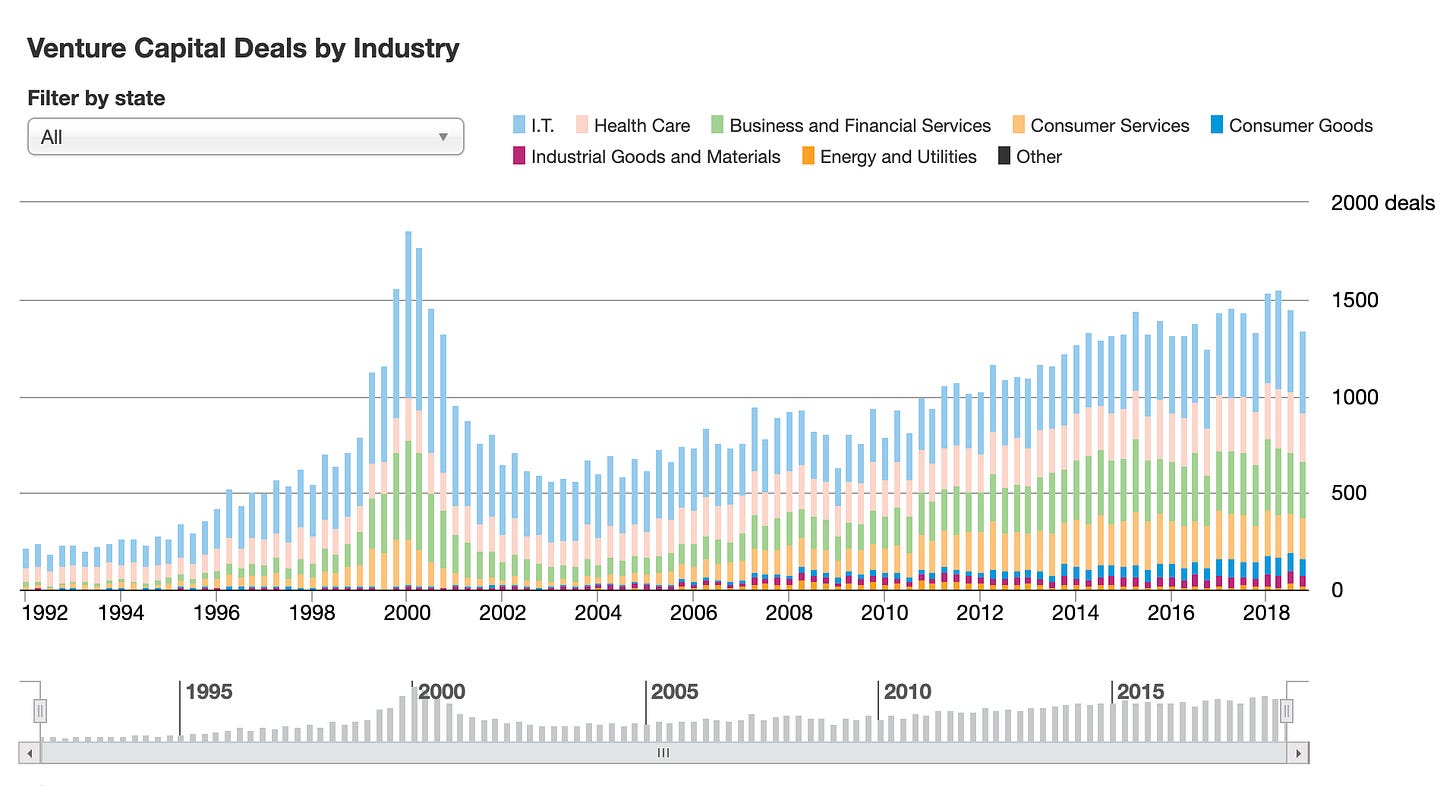

Venture capital in America does not invest much in manufacturing. Sometimes, even cool and attractive hardware innovations — Space and Robotics — have faced substantial struggles attracting VC interest and raising funds. If that is the case, you can imagine that there is no interest in making large investments in boring run-of-the-mill products like auto glass or solar panels.

Power Law rules everything in the valley. VC firms would love to invest in winner-take-all markets — manufacturing is patently not one of those markets. So, we end up with a plethora of predictably similar apps or one more SaaS replica.

I shouldn’t be unfair. While there are many excellent individual VCs who have been thoughtful and patient with such investments, they are in a small minority (and are probably not well known as the ones on social media). It is a hard sector to invest in, and many firms that have invested are holding some losses. The true cost is dynamism. Founders and entrepreneurs in hardware sector are hamstrung by the lack of avenues and enthusiasm for their ideas.

One thing that would make manufacturing sectors attractive to the VCs is eventual public market appreciation. Unfortunately, the public market’s appetite to fund manufacturing has remained fickle. In fact, almost all of S&P 500 growth has been entirely driven by what’s often called the Magnificent Seven (Meta, Alphabet, Tesla, Nvidia, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft). S&P 500 without the Magnificent 7 had barely moved, even before the current tariff crisis hit. (In earlier posts, I wrote about NVIDIA’s patient bet on hardware and about Apple’s move out of hardware into Services).

Is Private Equity our savior when it comes to manufacturing operations? There is much less to be said about Private Equity investments, which have, unfortunately, heavily focused on financial restructuring than operational restructuring to create value.

What about public capital, say, US government funding? Remember Solyndra whose government funding was controversial, even before its bankruptcy? The US seems to be in a period of skepticism about the role of government. Unlike the Post-War era and the 60s Space Race era, the US government today lacks the imagination to make costly science and engineering bets to fund large scale investments. In a future post, I will write about how giants of the semiconductor industry, like TSMC, are a byproduct of the less-known but visionary council called the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) a research and development institution founded in Taiwan in 1973, but that is for another day.3

What about foreign capital? Well, I think it is fairly clear that we are in an era of increasing economic division along national lines. We are going to see a phase in which Europe, Japan, China, India, and many other countries are going to invest more in their national and regional interests, rather than aid others.

3. Not Much Respect for Work.

One thing I know from experience is that factory work is tiring, arduous and boring. No person who worked in a factory all their life wants it for their child. People work not only for their livelihood, but also for respect.

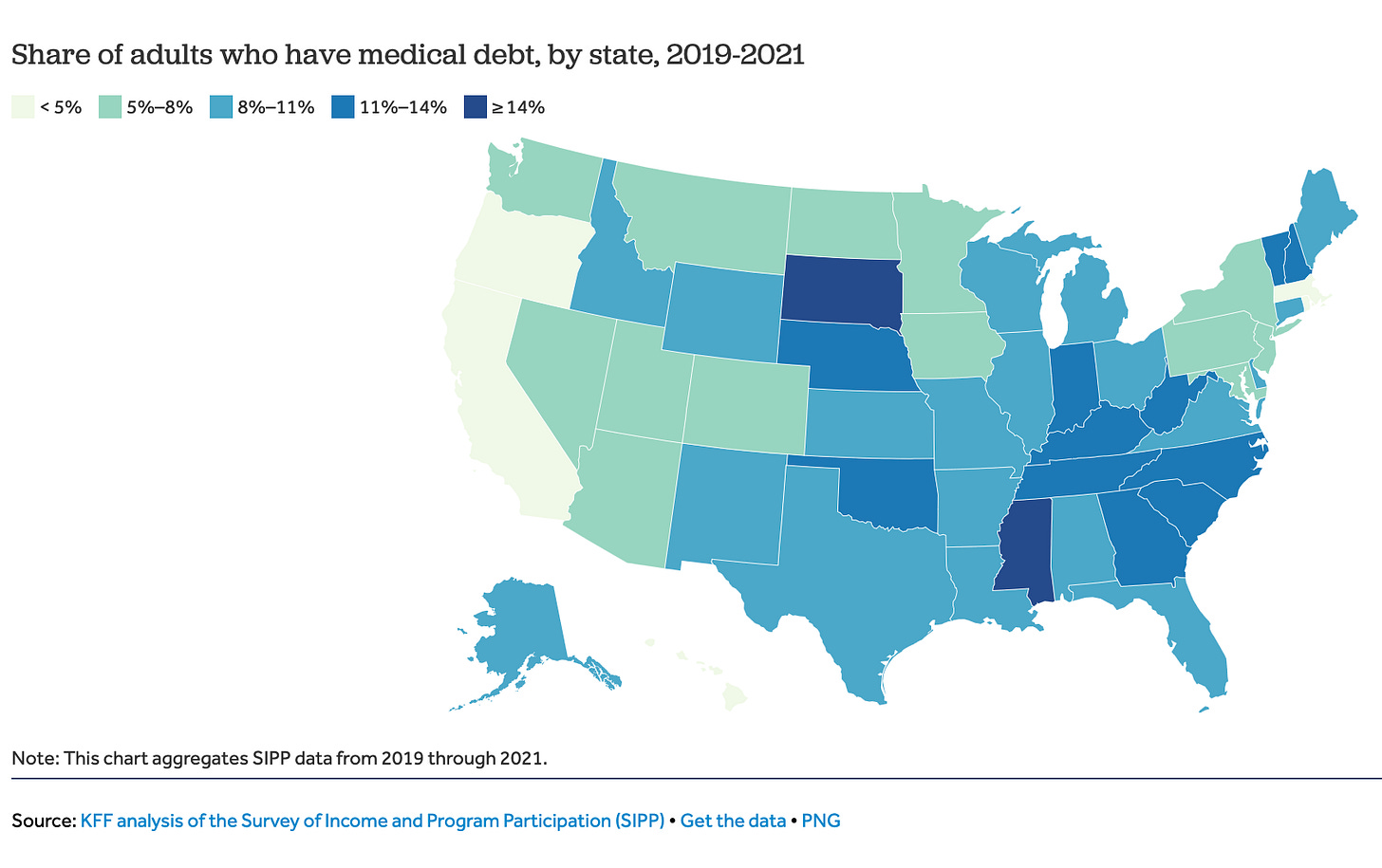

Manufacturing jobs are dull, dangerous and dirty. To accommodate people to work in such careers, there has to be a good safety net. Current manufacturing jobs don’t offer that. Most people want (a) good healthcare and (b) good education for their children.

Let’s take at the education and healthcare available for working families. There is a significant teaching shortage in the US (more than 55,000 school teaching jobs are open due to lower salaries, lack of administrative support, and poor working conditions) — and yet there is serious consideration of shutting down the Department of Education. In health care, more than half the registered nurses in the US, leave their jobs within their first two years due to burnout (US Chamber of Commerce, 2025).

The perpetual disregard for manual labor has destroyed the possibility of community building.

Manufacturing jobs are a conduit for dreams. They bring means of livelihood and respect to people. They allow them to hope for their families. Manufacturing jobs teach people discipline, perseverance and people management, helping people to move up the value chain. Eventually, up-skilling happens. My favorite example on up-skilling is the growth of Shenzhen. In 1990s, Shenzhen was a low quality apparel manufacturing location. Over the decade, the most industrious among the workers became experts in running the shift, then running the plant, and eventually running the supply chain for any hardware product. Now, Shenzhen is the hardware capital in any value chain.

4. NIMBY: Not In My Back Yard.

Resistance to building infrastructure has been one of the sore points in the recent US infrastructure growth. Most people don’t want buildings in their backyards. It has been extremely easy to build empty large warehouses and data centers in empty lands (due to highly motivated capital investments), but it has been hard to build plants and manufacturing centers where people work, live, and commute.

The Cape Wind Project was a wind farm project in Nantucket Sound that was supposed to generate 1500 gigawatts of electrical power a year. Ironically, the project died because both Senator Ted Kennedy (MA), the most liberal member of the Senate, and William Koch, one of the Koch brothers, (who commonly fund right wing causes) were (separately) strictly against the project because of environmental reasons. (The joke was the view from their summer homes would be utterly destroyed.) My main point is that not wanting something in their backyard motivates people regardless of their political persuasion.

The United States’ sociopolitical system is highly localized, despite the obsessions of news and cable TV, which focus heavily on events in Washington DC. Local school board, activist parents, housing board neighbors, and community organizations often control, litigate, and dictate growth. So the building of factories and manufacturing facilities come under signifiant stress, lawsuits, and delay. These impediments slow industrial growth across critical supply chain infrastructure sectors from building high speed rail networks to modernizing our ports.

5. Manufacturing cannot escape Automation.

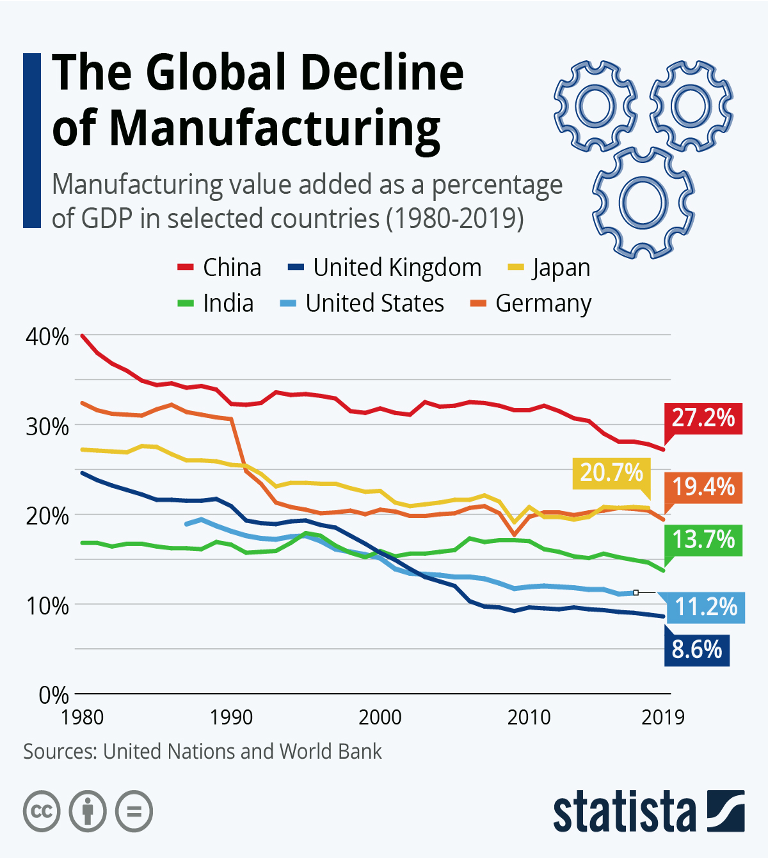

The least well kept secret in the world is the following. Almost everywhere, manufacturing is no longer the main contributor to the GDP. Manufacturing as a part of GDP has been falling in every developed country.

When looking at the figure above, it is immediately noticeable that even in China the percentage of manufacturing GDP has declined. The (only) kids of parents who once worked in factories now want to begin entrepreneurial ventures. Also noticeable are the effects of Brexit and German Unification. In any case, the countries that do have a sizable portion of their GDP in manufacturing — Japan and Germany — continue to invest in their human capital in the industry.

I want to leave you with two points on the above picture, presented as future perspectives.

No country can afford to be the factory for the world.

In the future, manufacturing will continue to be a small portion of GDP in every country. Minerals, resources and talent is distributed across the world in a myriad of ways — the only way for growth is to specialize on one’s skills to overcome constraints through trade.

Manufacturing Today, Knowledge Work Tomorrow.

Automation has truly made manufacturing productivity and scale possible. We are now more efficient and faster at making physical products in large volumes. Similarly, AI-automation is going to pervade knowledge workflows. We will see the same type of productivity growth (and challenges) in the knowledge industry. So whatever challenges we face in supply chains today are precursors to the white collar challenges that are coming up.

Back to Seneca, again, who wrote:

There is no favorable wind for the sailor who doesn’t know where to go.

We are at crossroads, and it is unclear what the future holds. But it is time to invest in human capital.

Tariff and Hindi word (तारीफ) are from the same word.

Taarif (तारीफ) implying praise is truly a Urdu word meaning appraisal, coming to Hindi/Urdu through Persian from Arabic root ta’arifeh. A ta’arifeh which was a list of things that one should know, ie an appraisal of a price list or inventory list.

Moving west through trade, ta’arifeh went from Arabic to Spanish to French tarif which is a price list or fare or price-rates. Eventually the French usage moved to English and eventually became tariff that denotes tax rates. (Not a linguist, so happy to be corrected).

Incidentally, Apple shipped 600 tons of iPhones out of India, before the tariffs struck. Apple factory is also located in South India, south of the city of Bengaluru.

https://www.reuters.com/technology/apple-airlifts-600-tons-iphones-india-to-beat-trump-tariffs-sources-say-2025-04-10/

In the 1980s, ITRI initiate the very large-scale integration (VLSI) project. Morris Chang started his tenure as ITRI President around this time.

I enjoyed the Selten reference at the outset. In circumstances like these, I often think of Kreps and Wilson's (1982) "Reputation and Imperfect Information," where building a reputation of toughness can help the emergence of cooperative equilibria. One problem of the Trump administration is that flip-flops follow initial claims of toughness, resulting in chaos.

Senthil, thanks for thoughtful pieces regarding actions that seem to be done in anything but a thoughtful mode! I'm sure there's some model that accounts for these wide swings in action, but it must be unsettling to have to analyse what's currently going on. A question is how much the electoral process and the executive powers currently being exercised really reflect the US 'strategy' in some fundamental way. I find it hard to assess the various segments of society in a country going only by how their governments behave (as true in India as anywhere else).